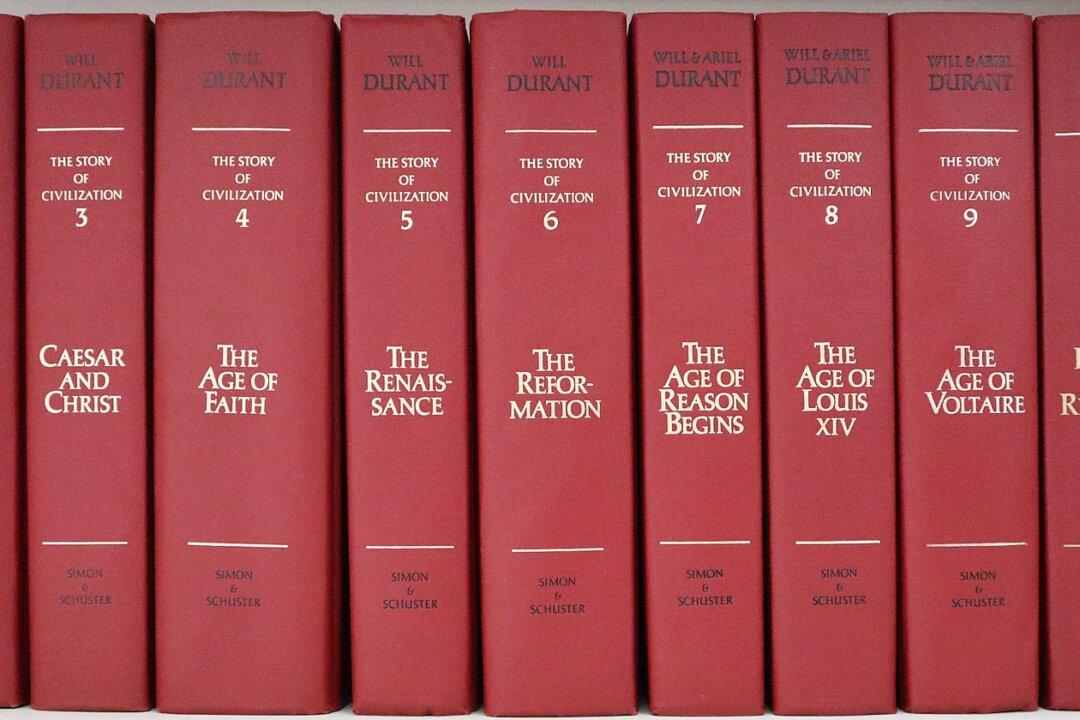

Eleven volumes in all. Total length: approximately 22 inches. Width per volume: 6 3/4 inches. Height per volume: 10 inches. Weight of volumes combined: 36.6 pounds. Number of pages: 8,945. Number of words: somewhere around 4,000,000. Such are the dimensions of Will and Ariel Durant’s “The Story of Civilization,” published between 1935 and 1975.

For 20 years, “The Story of Civilization” sat on my shelves. Three times I boxed up this Himalaya of History and moved it with my other belongings to a new home. When I was teaching history to homeschoolers, I might open one of these volumes to seek out a pertinent person or event, and take some notes for class, but otherwise there they squatted, forlorn and ignored, good only for decoration and for gathering dust.