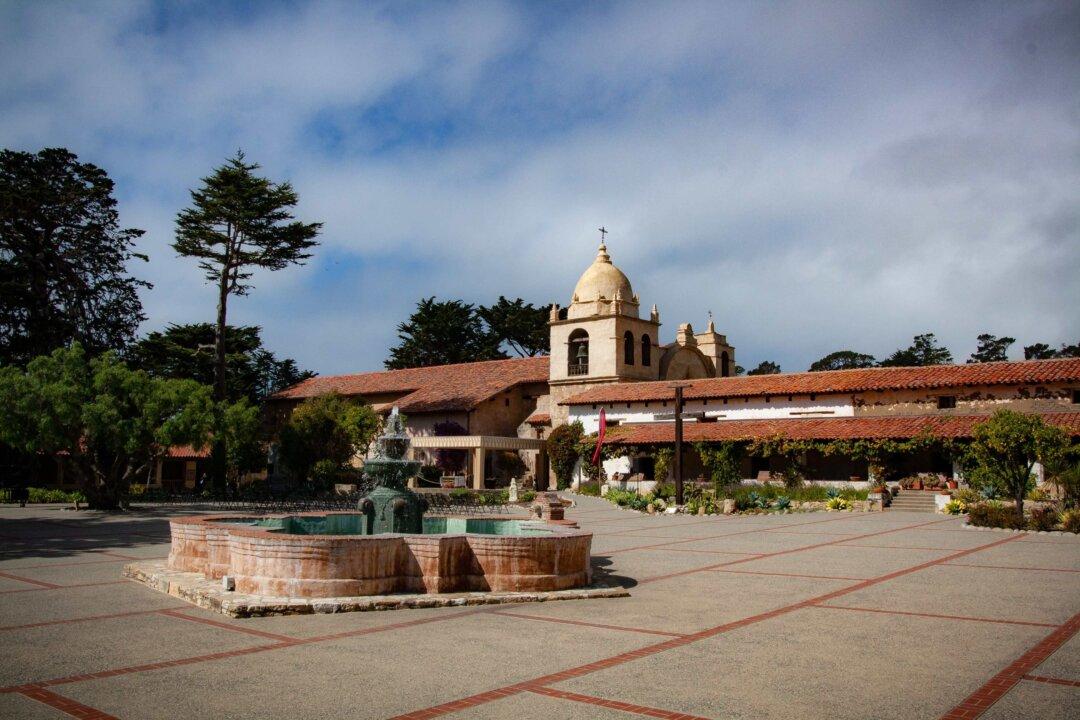

Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo, or the Carmel Mission, was second in the chain of Spanish missions in California. Considered to be one of the most well-restored of the chain, Carmel Mission just celebrated its 250th anniversary after being founded in 1771. Named for Saint Charles of Borroméo, a 16th-century Italian cardinal, the mission’s beautiful condition today makes it difficult to imagine the extreme disrepair it had fallen into less than a century after its founding. As California’s complex history of ownership unfolded, the church and surrounding structures experienced chapters of ruinous dilapidation and abandonment before nearly a century of restoration efforts took place. Presently, Carmel Mission is a national historic landmark, a group of museums, and an active Roman Catholic church.