In this column, “The Masters’ Thread” (ept.ms/mastersthread), artists share their thoughts about how one master’s piece inspires their current work.

I can still recall the first time I saw the masterworks of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). I was fresh out of art school, 23 years old, and had recently decided I needed more technical guidance, so I fell into the world of classical art training. Paul Ingbretson, my first ever classically minded teacher, had a library of art books that opened my eyes to artists that I hadn’t appreciated or even known existed.

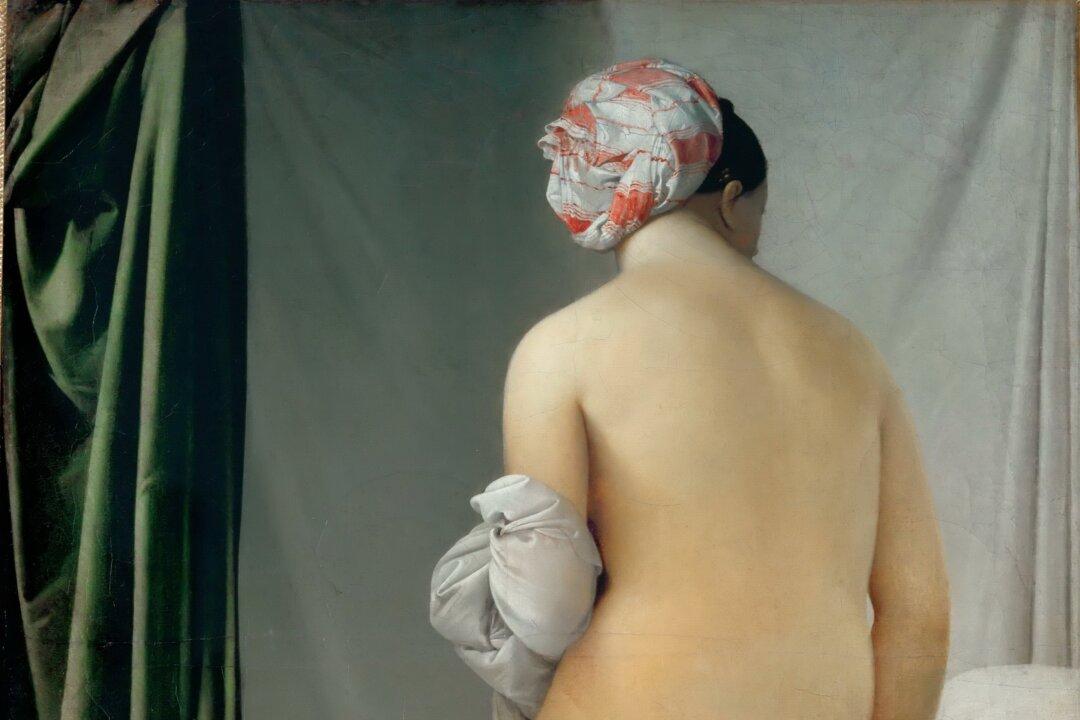

On his library wall, there was a poster of Ingres’s “Princesse de Broglie,” and in his collection, a monograph full of Ingres’s paintings and drawings. I was perplexed by the work. I had a stubborn resistance to liking it, but I could not stop opening the book or stop staring at the poster—his lines, his forms, his completely flawless modeling of the forms. At the time, I found it stuffy and academic, but unquestionably the most consistently beautiful art I had ever seen.

That was nine years ago. Since then, I have been humbled many times over, realizing that my voice in art has been formed by first listening to the wisdom of those masters who paved the way.

“But how do I know how much to absorb of them before losing myself?” This common question among artists was ringing in my ears as I struggled through cast drawing and learning the seemingly impossible systems of basic drawing, anatomy, and color theory while training at Grand Central Atelier in New York. My opinion is this: There is no limit to what the great masters can teach us if we are willing to be free in our curiosity. I am now constantly asking myself to take, steal, and enjoy what I like in great works. What do these masters have that I desperately want? How freeing it is to realize that their progress and mastery is ours to utilize.