Forty-one years ago this March, the citizens of Fort Wayne, Indiana, were in a desperate battle against rising floodwaters threatening to utterly engulf their city.

And they were losing.

Mountains of piled-up, heavy winter snow—81 inches had fallen that season—combined with an unseasonably warm March thaw, had swollen the St. Joseph, St. Marys, and Maumee Rivers to historic and cataclysmic levels.

Already, after four days of struggle, much of the city was under water and evacuations were underway. Before leaving their homes and businesses, citizens piled furniture high in their living rooms and hung bags of belongings from ceiling fixtures. Rising floodwaters were sweeping in the front doors and slushing out the back. All around the city, levees became so waterlogged they started to leak; 69-year-old dikes were failing.

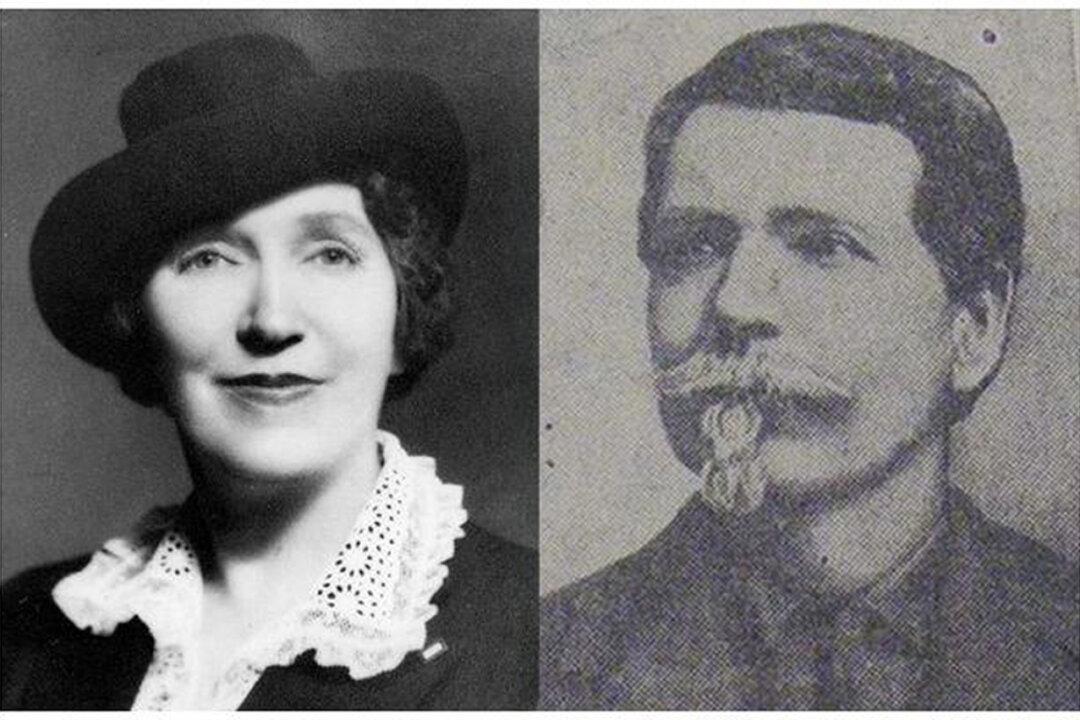

With the heart of Fort Wayne in eminent danger as water continued to rise, and no more civil or governmental resources left to help, an exhausted yet intrepid Fort Wayne Mayor Winfield “Win” Moses did the unthinkable.

He called the kids.

“They were the only hope we had,” Moses said recently in an interview. Within hours, hundreds—then thousands—of Fort Wayne school children began answering the “urgent need” for help, Moses said. Boys dressed in corduroy slacks and sweater vests, and girls in ruffled peasant blouses, overalls, and monogrammed sweaters filled the Allen County War Memorial Coliseum and lined the 8 miles of city dikes.

And in six days, some 10,000 school children had filled, hauled, and stacked more than a million sandbags, reports claimed—used to buttress the leaking dikes against the three rivers that were drowning their town. Teenagers out in the freezing rain—some with no boots or gloves—were passing sandbags and singing, hour after unrelenting hour, floodlights illuminating their work.

But they beat back the rivers. “It was a children’s crusade, no doubt about it,” Moses recalled. His memories have clearly not receded, unlike the floodwaters. He estimated that teenagers comprised 60 percent of the flood-fighters.

“I meant it then and still mean it today,” said the retired Indiana pol now living in North Carolina. “The kids of Fort Wayne saved our city.”