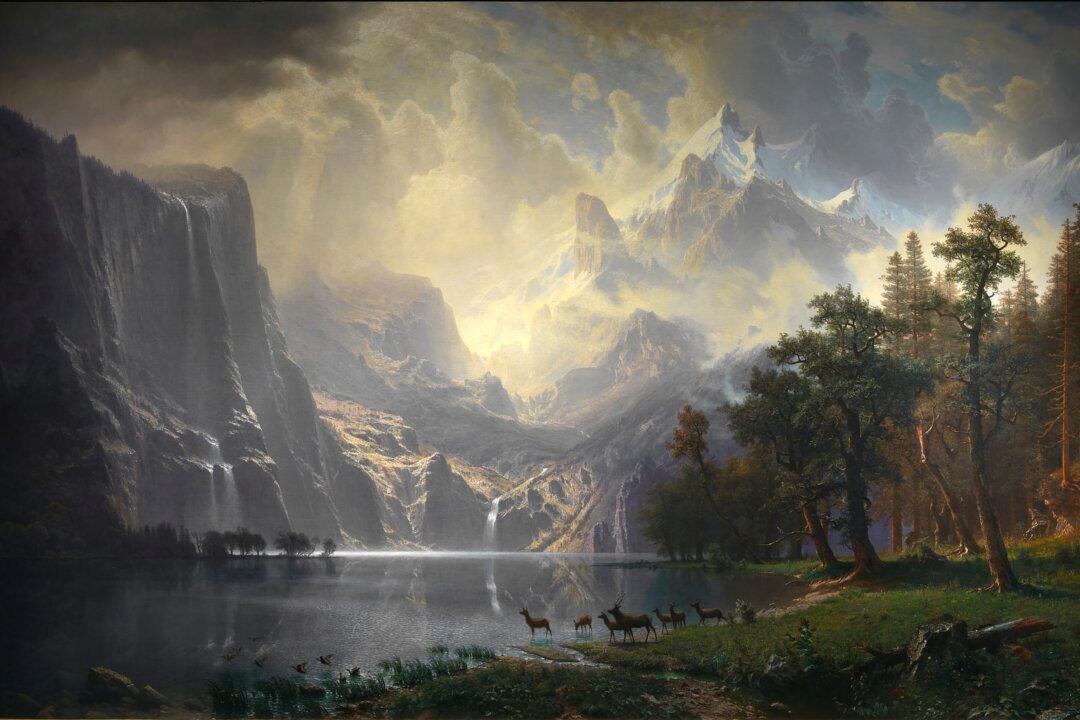

Have you ever had a painting show up at different times in your life when you needed it most?

At Penn State in 1967, in the auditorium for Professor Jim Lord’s art history survey class, a large screen spanned the width of the stage. He would flash up slides from different artistic eras—some older, then more modern pieces. Some of the abstract art with splotched canvases were forgettable.