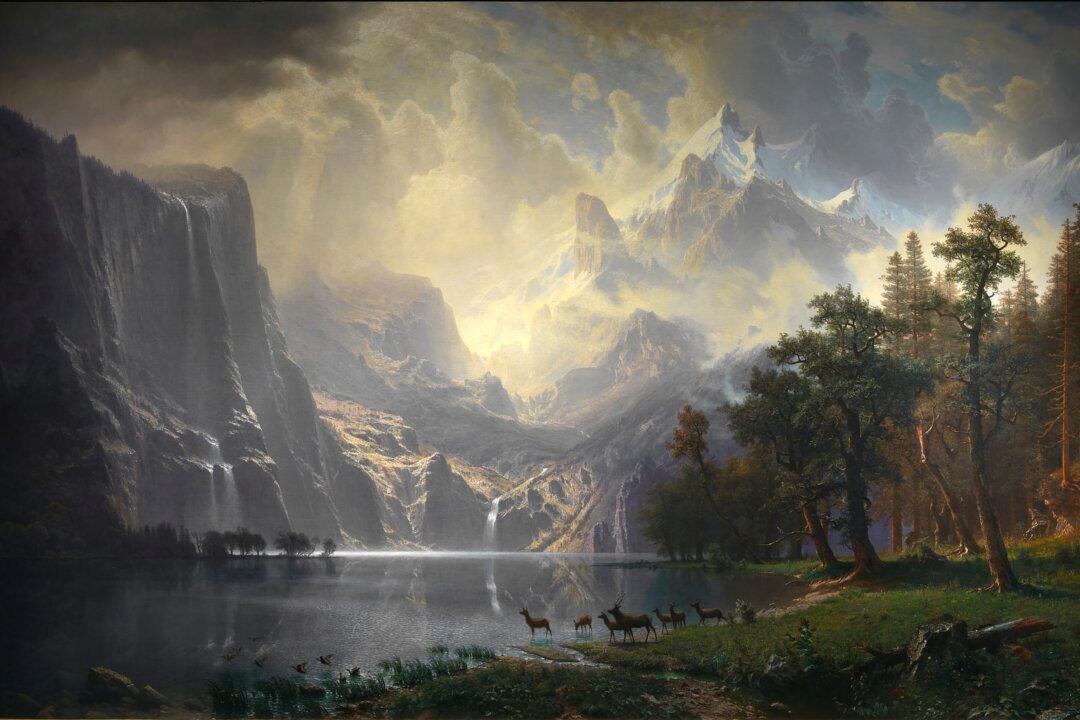

Several years ago, I commissioned a fine artist to paint my girlfriend’s favorite photo of her two teenage daughters. They were at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, one with her arm extended, tossing a coin into a large water bowl.

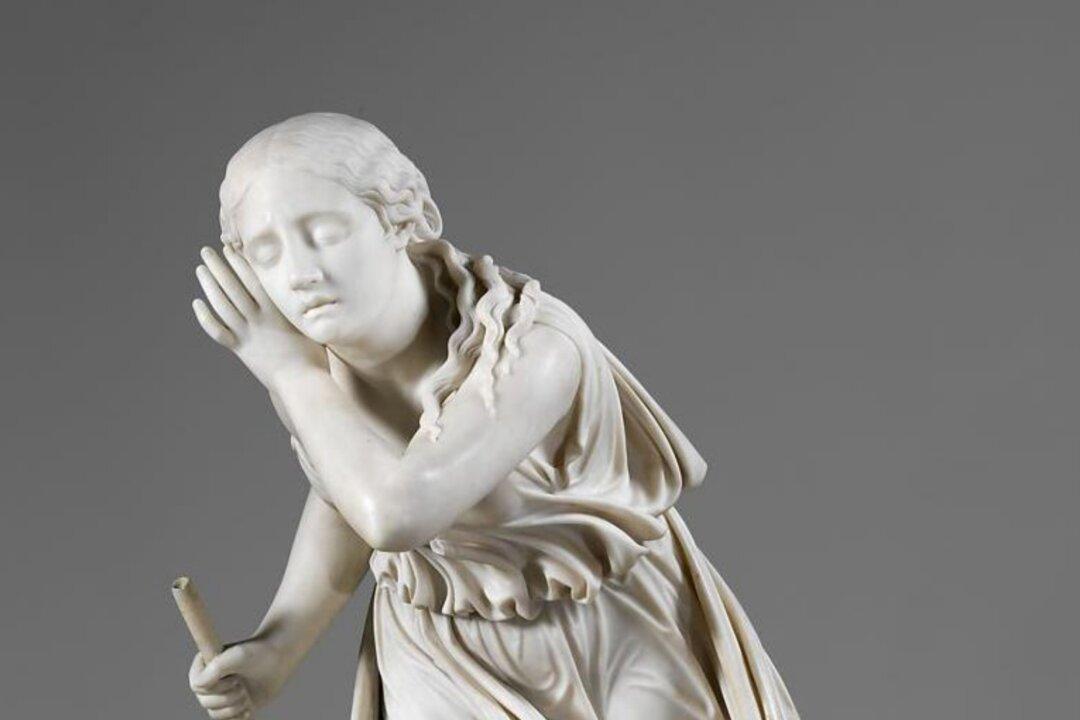

When the painting was completed, I was surprised that the artist had replaced the bowl with a statue. He said the sculpture added depth and enhanced the picture. I had to agree. But what was the piece? Research revealed that it was “Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii.”