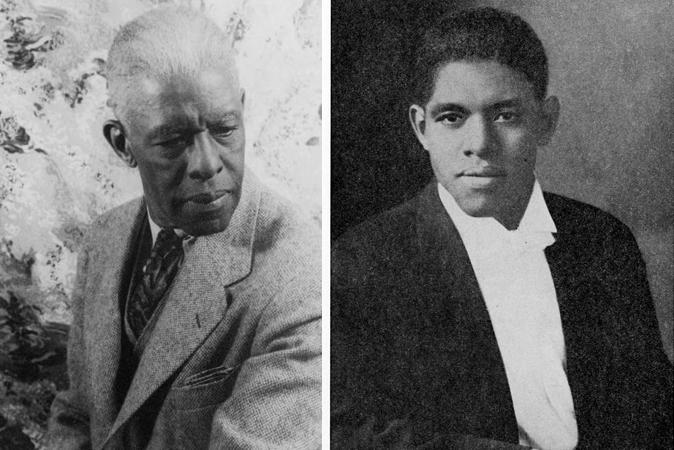

The book “Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor” by Christopher A. Brooks and Robert Sims begins with a remarkable scene. In 1926, the famous African-American singer traveled to Georgia to meet with Joseph Mann, who had owned Hayes’s mother and other relatives and on whose property the singer had been born.

Hayes wanted information about his family history and learned that some of his ancestors were known for their singing ability. At the time of the meeting, Hayes was prosperous and the former slave-owner was destitute. The meeting was cordial, especially considering that Mann had been brutal toward his slaves and had had Hayes’s maternal grandfather beaten to death for running off. Hayes had the satisfaction of buying the property and then informing Mann that he could stay on for free as a tenant.

After that prologue, the biography goes back to the beginning of the singer’s life. From an impoverished background, Hayes (1887–1977) overcame many hardships, including the early death of his father. His deeply religious mother was an inspiration as was the church. His first exposure to classical music was hearing a recording of Enrico Caruso, after which he decided to pursue singing as a career.

This took extraordinary determination since there was no precedent. The South was segregated; and even in the North and in the rest of the world, opera houses and symphony orchestras did not perform with black artists.