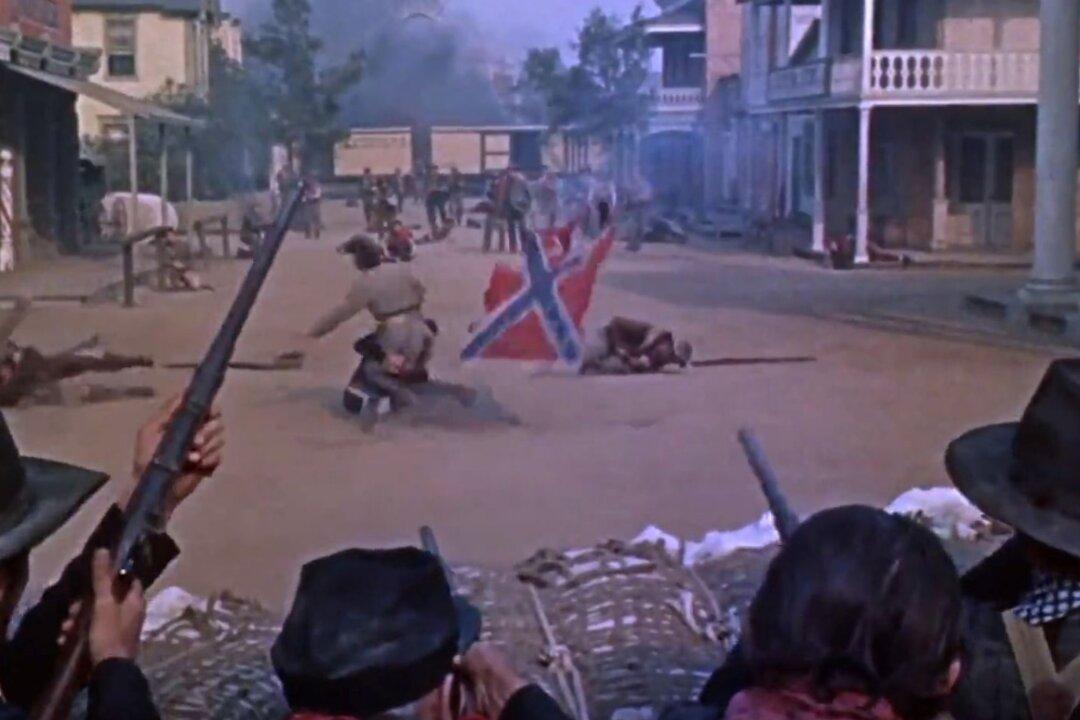

Not Rated | 2h | Adventure, Romance, War | 1959

For as many Western films as celebrated director John Ford made, it’s interesting that he produced only one wholly dedicated to the Civil War. (He did touch on the Civil War in 1962’s “How the West Was Won.”) “The Horse Soldiers” (1959) was his only film about the conflict, and he couldn’t have chosen a more compelling narrative to base the film on.