On September 23, 1916, the young American pilot flying a French Nieuport 17 above Verdun spotted a German two-seater Aviatik and raced, as he so often had, to engage the enemy in combat. As he dove from 10,000 feet on the German aircraft, an explosive bullet fired by the Aviatik’s tail gunner tore into his chest. The American died instantly, and his aircraft crashed in between two trenches in a field in France, where artillerymen recovered his body.

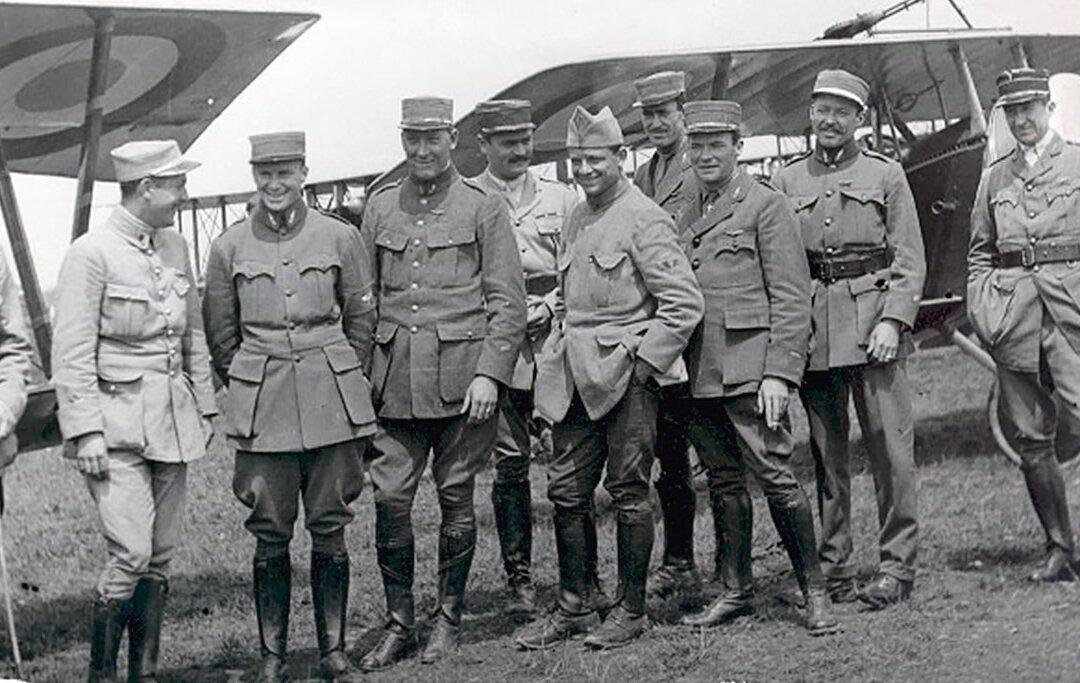

The French government paid this brave dead pilot its highest honors, gave him a funeral that included several hundred military personnel, made his grave a shrine, and later built a monument to him and other American pilots. At the graveside service, Capt. Georges Thenault, commandant of the airman’s unit, said of his fallen comrade, “His courage was sublime. … The best and bravest of us is no longer here.”

Following his death, he was hailed as a hero throughout France and America, a celebrity of his day. After the war, his likeness was featured on bubble gum cards, stories and comic books celebrated his daring and heroism, and poets like Edgar Lee Masters memorialized him. Places as distinct from one another as Asheville, North Carolina, the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), the Pantheon in Paris, and other localities paid homage to this fallen warrior with plaques and memorials.

Yet today, Kiffin Rockwell rests in his grave in France largely forgotten by his fellow countrymen.