Charles Francis Hall (1821–1871) was born in Vermont, moved with his family as a child to New Hampshire, and then moved westward to Cincinnati when he married. It was in Cincinnati that he developed his entrepreneurial spirit by founding a seal-engraving business and then starting two newspapers, the Cincinnati Occasional and the Daily Press. During his Cincinnati days, his business mind was aroused by the curiosity of exploration.

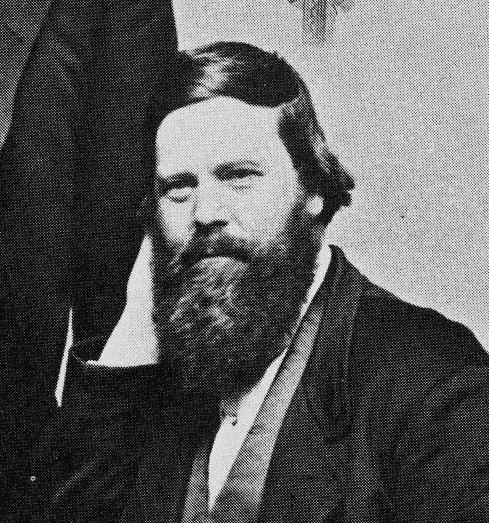

Charles Francis Hall in the only known photograph taken in Washington in the winter of 1870. Public Domain