Since the days of Aesop, animals have been used as vehicles by which humankind has addressed its moral, ethical, and cultural identity. For some, this serves to misrepresent animals, privileging anthropomorphism at the expense of the more sensitive address of animal sentience and welfare. For others, this approach allows humans to circumvent their own social taboos to reveal not merely fresh insights into what it is to be human, but also humanity’s intrinsic relationship to animals, with animals, and as part of nature.

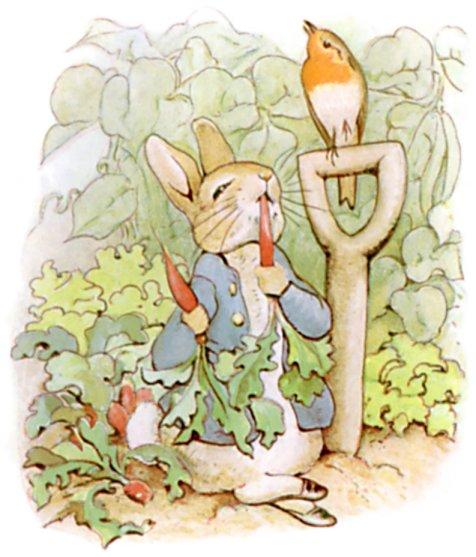

Beatrix Potter enjoyed the work of poet Edward Lear, who specialized in nonsense verse and who wrote about a “Remarkable Rabbit.” Potter thus decided to create “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” the story of a mischievous rabbit, who disobeys his mother to play in Mr. and Mrs. McGregor’s garden, despite all its apparent dangers. From the outset, it was Potter’s intention to use the story to show both human characteristics and animal behavior.