Thomas Clark Jr. had always been interested in his uncle George, a U.S. Navy sailor who died on the USS Oklahoma when Pearl Harbor was bombed. After Clark served in the U.S. Army in 1968 and 1969, his maternal uncle’s fate became a lot more significant because he understood what war was like.

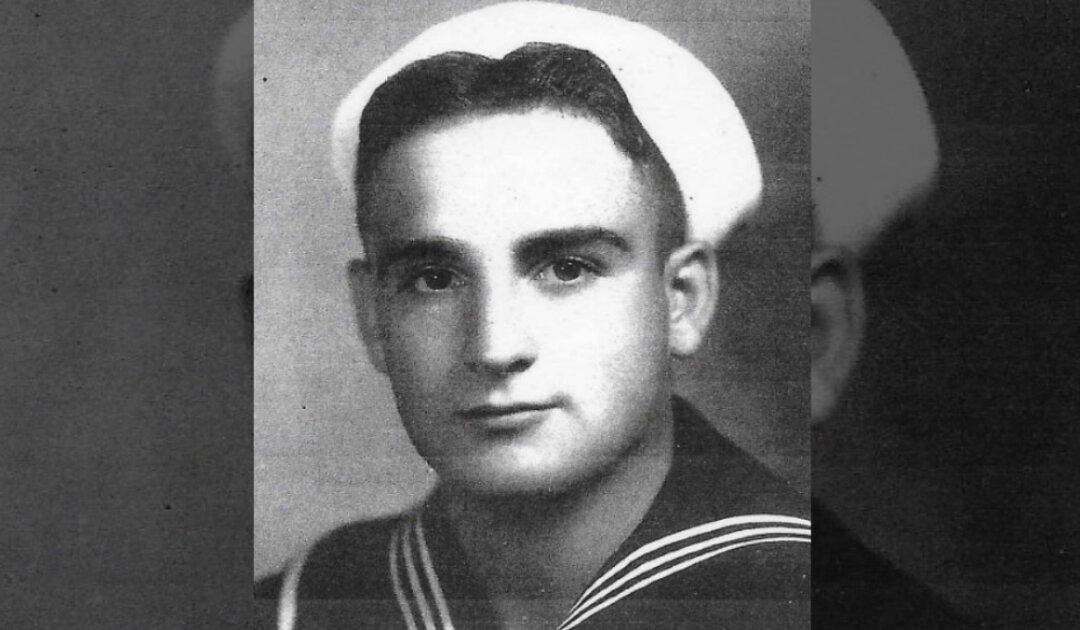

Navy Electrician’s Mate 3rd Class George Harvey Gibson was 20 years old when Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japanese aircraft on December 7, 1941. Multiple torpedo hits caused the USS Oklahoma to capsize in 12 minutes, taking with it 429 sailors and crewmen, including George.