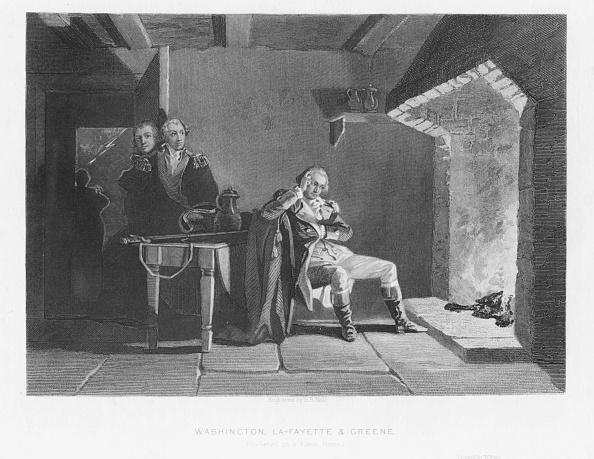

From a young age he walked with a limp, but that would not stop Nathanael Greene from achieving a distinguished military career during the War for Independence. In fact, after George Washington, Greene has been called by historians the “second best” American general in the Revolutionary War.

In his article, “The Most Underrated General in American History: Nathaniel Greene,” historian Russell Weigley says, “Greene’s outstanding characteristic as a strategist was his ability to weave the maraudings of partisan raiders into a coherent pattern, coordinating them with the maneuvers of a field army otherwise too weak to accomplish much, and making the combination a deadly one. [He] remains alone as an American master developing a strategy of unconventional war.”