Self-help, personal development, self-improvement, learning and development, education—we have a million and one names for this process, but what they all boil down to is this age-old spiritual idea of self-transformation.

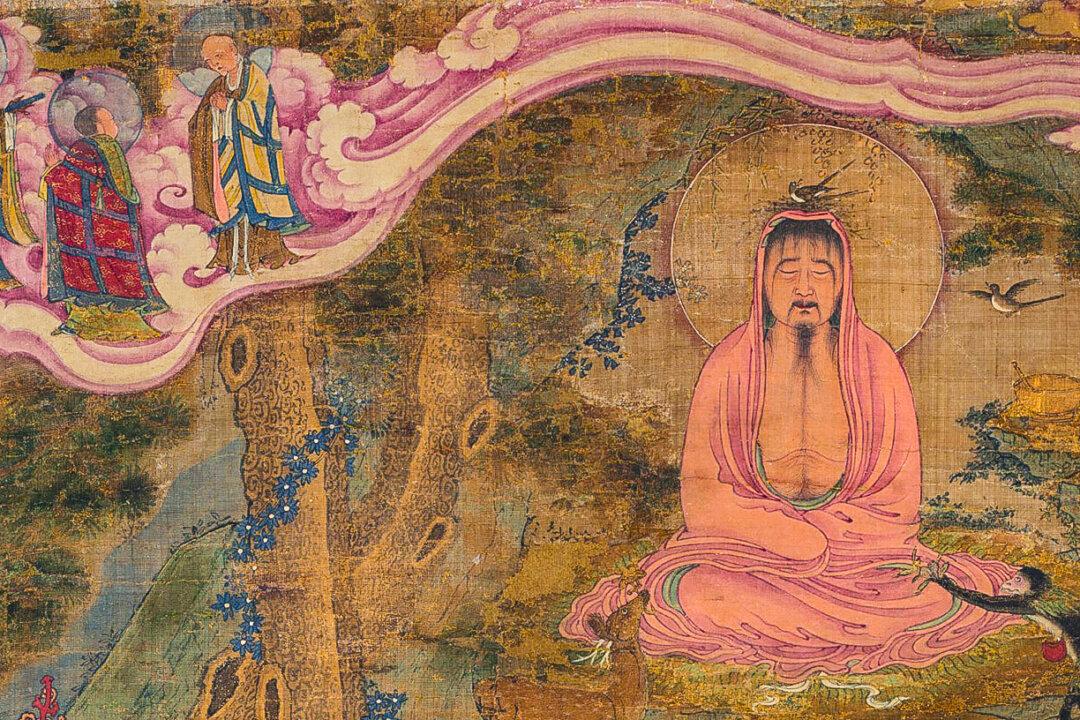

While the concept of religion is far too big to address in an article such as this, one broad truism that we might draw from the vast corpus is that virtually all the world’s religions, Eastern and Western, introspective and exoteric, big and small, revolve around this idea that human beings need mechanisms to help improve themselves, whether these be commandments, rituals, practices, abstinences, worship, or divine intervention—and not forgetting faith itself.