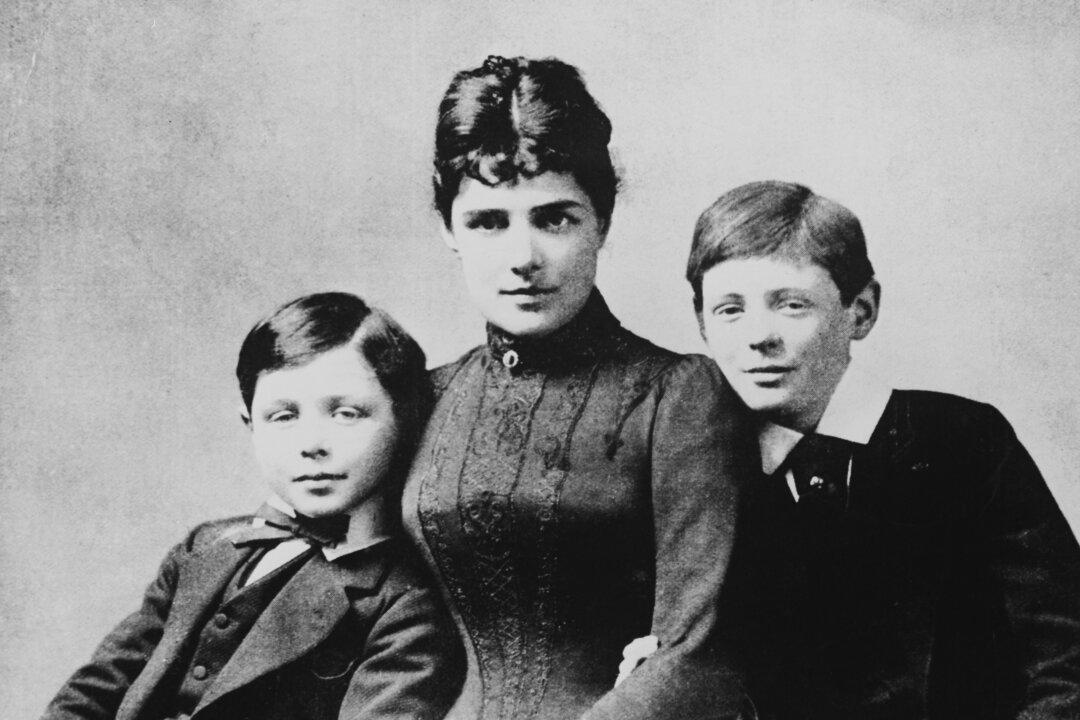

American-born Jennie Jerome Churchill and her British husband Lord Randolph would never qualify for any Best Parent of the Year award.

Though Winston adored his father, Lord Randolph rarely displayed any affection for Winston, considering him lazy and dimwitted. The distance between father and son was enormous. In “Churchill: Walking With Destiny,” biographer Andrew Roberts reports that after a family dinner in the 1930s, Winston said to his own son, “We have this evening had a longer period of continuous conversation together than the total which I ever had with my father in the whole course of his life.” Despite this note of condemnation, Winston revered the memory of his father.