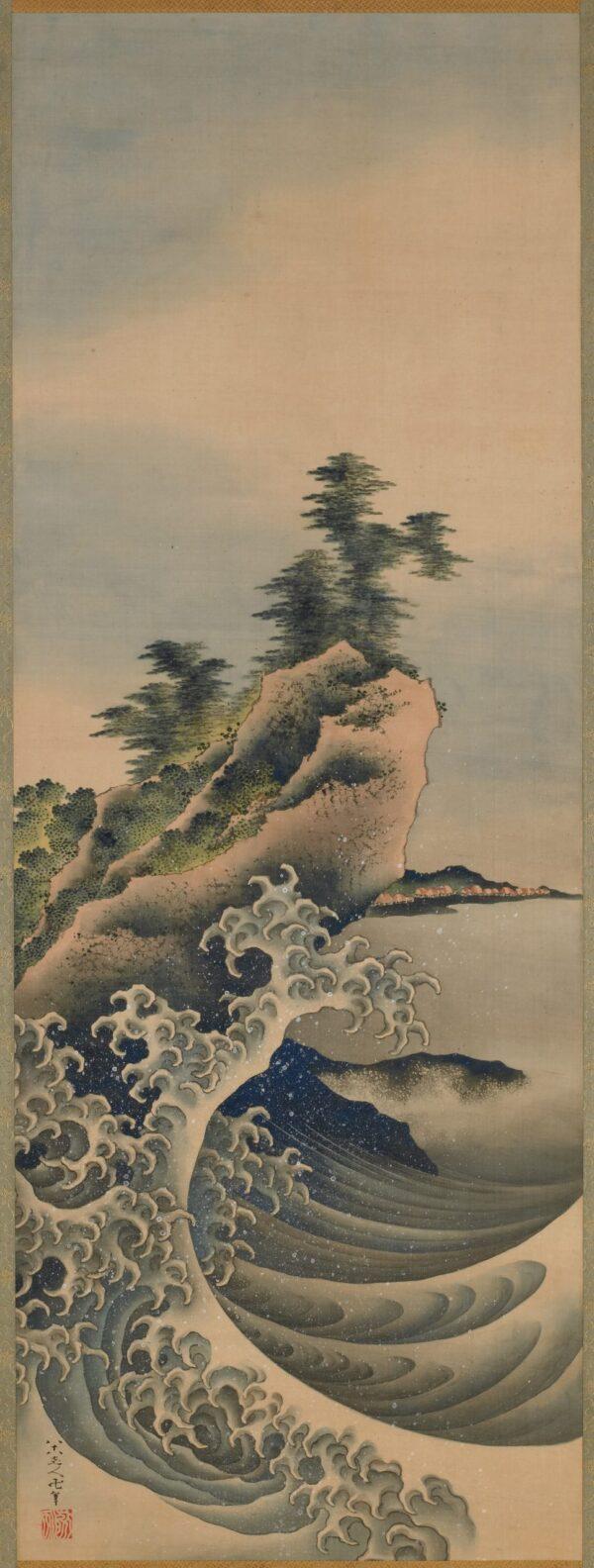

Many know Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai from his famous “Great Wave off Kanagawa” print. Yet Hokusai was “a man mad about painting,” as he proclaimed in one of his signatures, the Japan Foundation assistant curator of Japanese art, Frank Feltens, said in a phone interview.

Detail of "Breaking Waves," 1847, by Katsushika Hokusai. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk. Gift of Charles Lang Freer, Freer Gallery of Art. The Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery