This is the fourth and final article in this particular Dante series. We remember that we read Dante because he addresses the big questions of truth and reality, and we saw how in Hell the issue of free will is of paramount importance. Subsequently, we discovered that although Purgatory and Hell seem similar in that they are both places of suffering, they differ fundamentally. In the former, there is hope and ultimately beauty, whereas in the latter, there is only despair and profound ugliness. These differences reflect the choices that individuals make in their lifetimes, and these choices are themselves all part of a psychological mind-set or disposition.

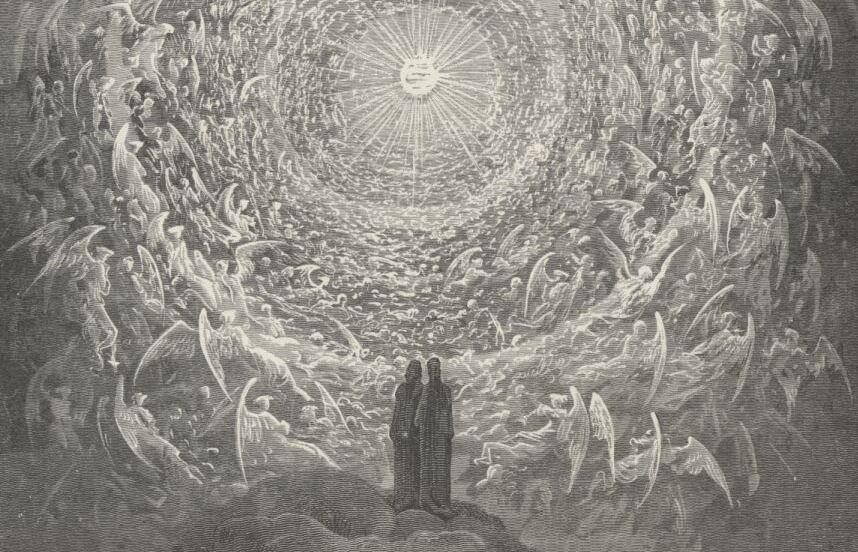

But what of Heaven, the third and final stage of Dante’s upward ascent toward God? Is that some boring place where we are destined to sit around listlessly singing hymns? How is it different from the other two psychological and spiritual places?