Disclaimer: This article was published in 2022. Some information may no longer be current.

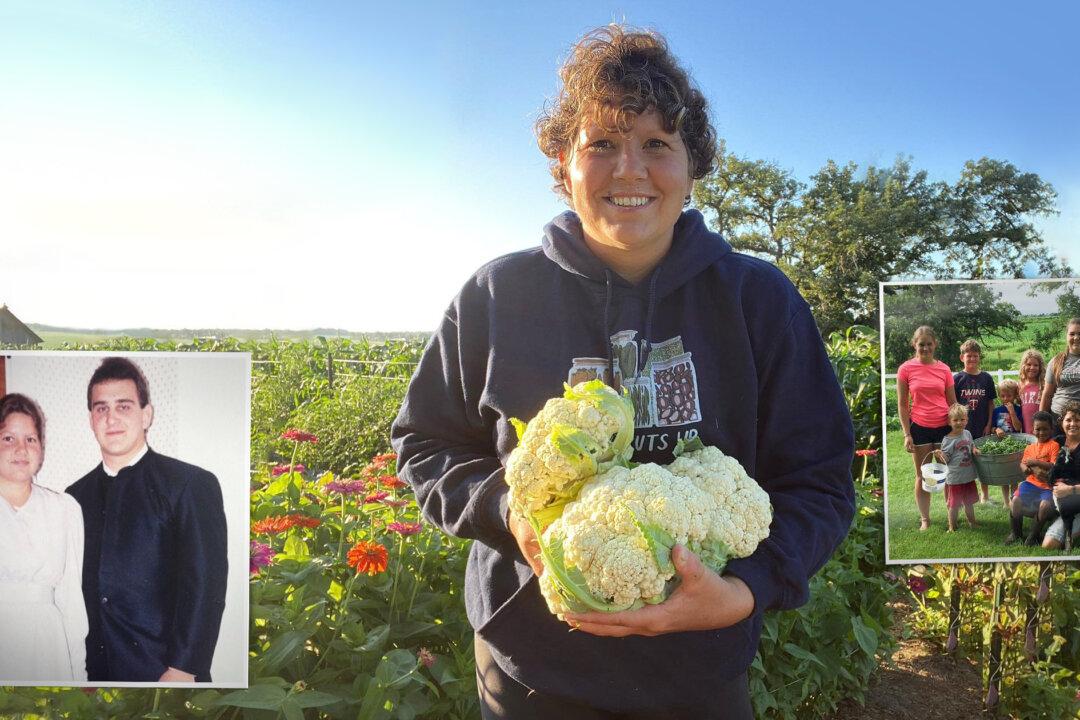

RuthAnn Zimmerman didn’t realize her sequestered way of life was trending online until after searching the hashtag “homesteading” on Instagram. Soon afterward, hashtag homesteading found her.