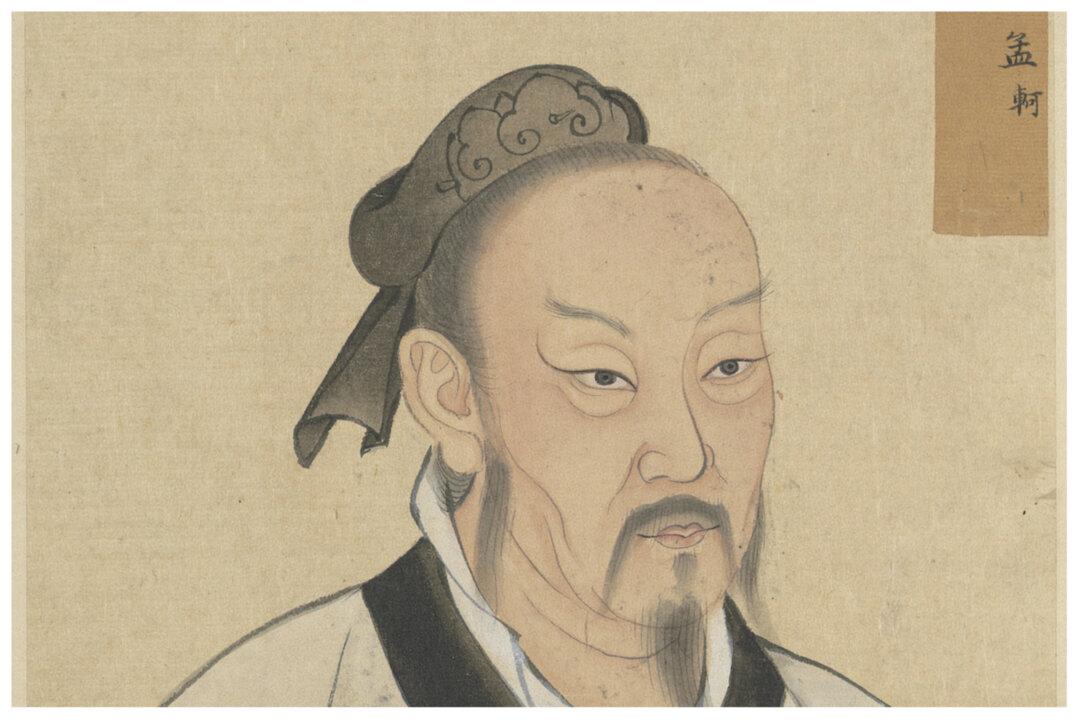

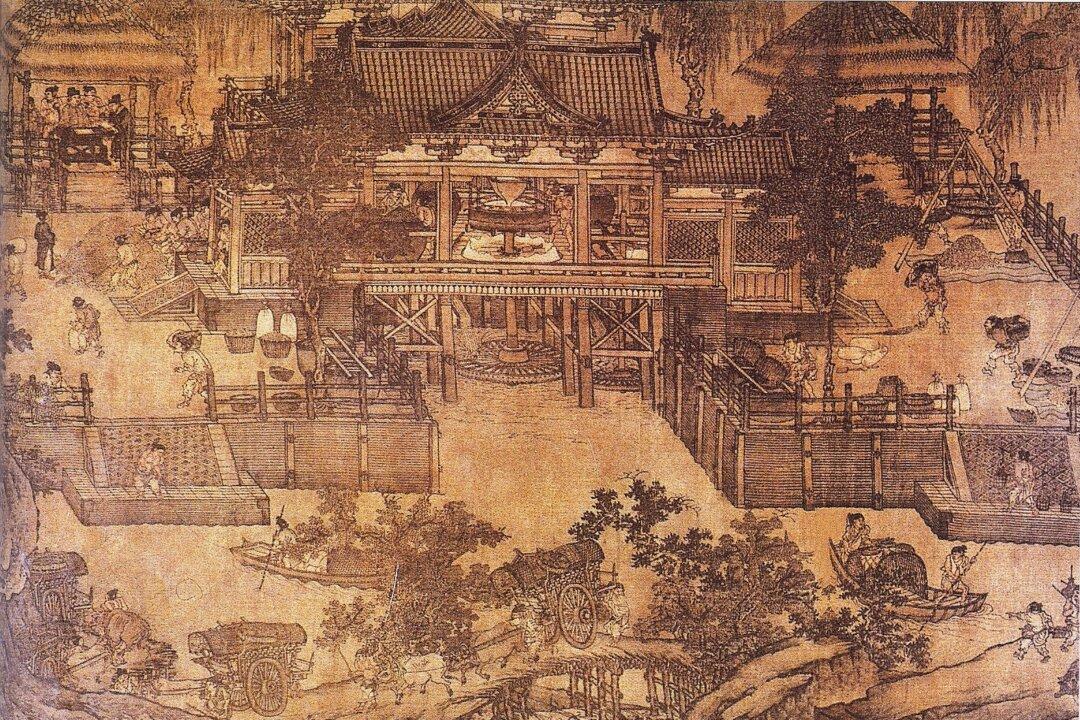

A very long time ago, a Chinese scholar wrote, “The people are the most important element in a nation; the land and grain come next; the sovereign counts for the least.”

That sovereign, moreover, should rule by the consent of those he governs, and if he’s a tyrant, the governed have every right to get rid of him, one way or another.