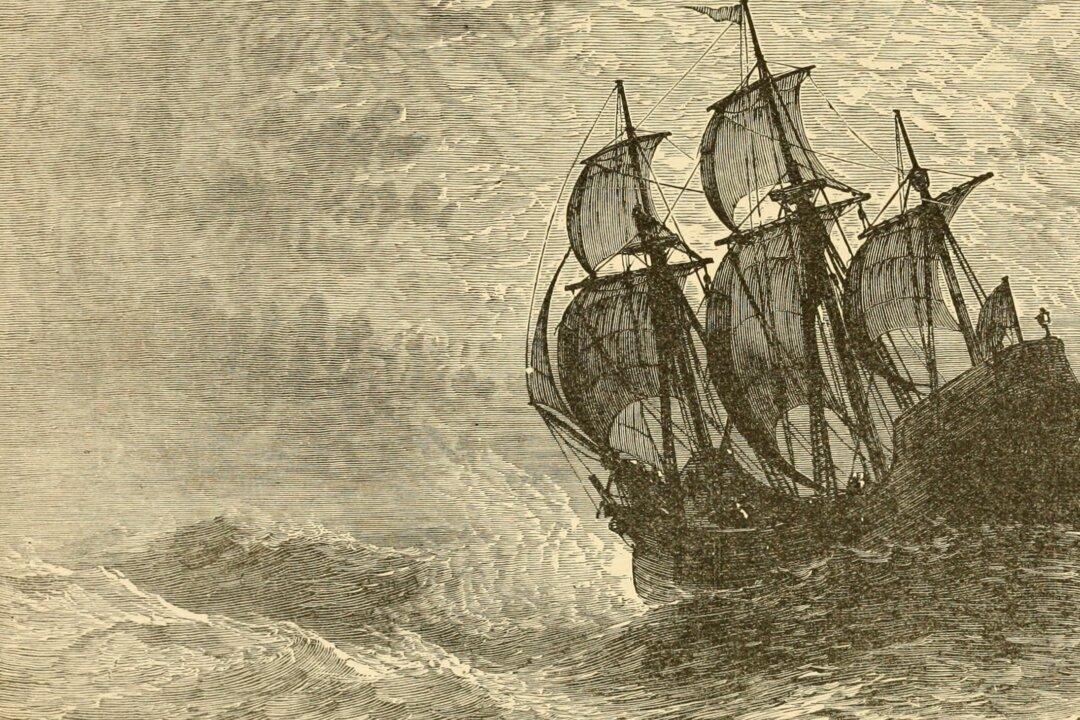

It is July 1620 in Southampton, England. Arriving into port is the Speedwell, a ship carrying a small religious group from the Netherlands. Anchored just off of the west quay of the town is the Mayflower, a larger ship with more passengers aboard, which is loading for a transatlantic voyage with the Speedwell. The passengers have permission and funding to start a trading settlement in the Colony of Virginia (which at the time extended much farther than the modern state of Virginia), under the control of the Virginia Company.

Despite the historical significance of the Mayflower, we know very little about the ship and its voyage. We only know its name from a document written three years after the voyage. At the time, the Mayflower was not notable or special. And because some of the passengers faced persecution for their religious activities, they probably kept a low profile.