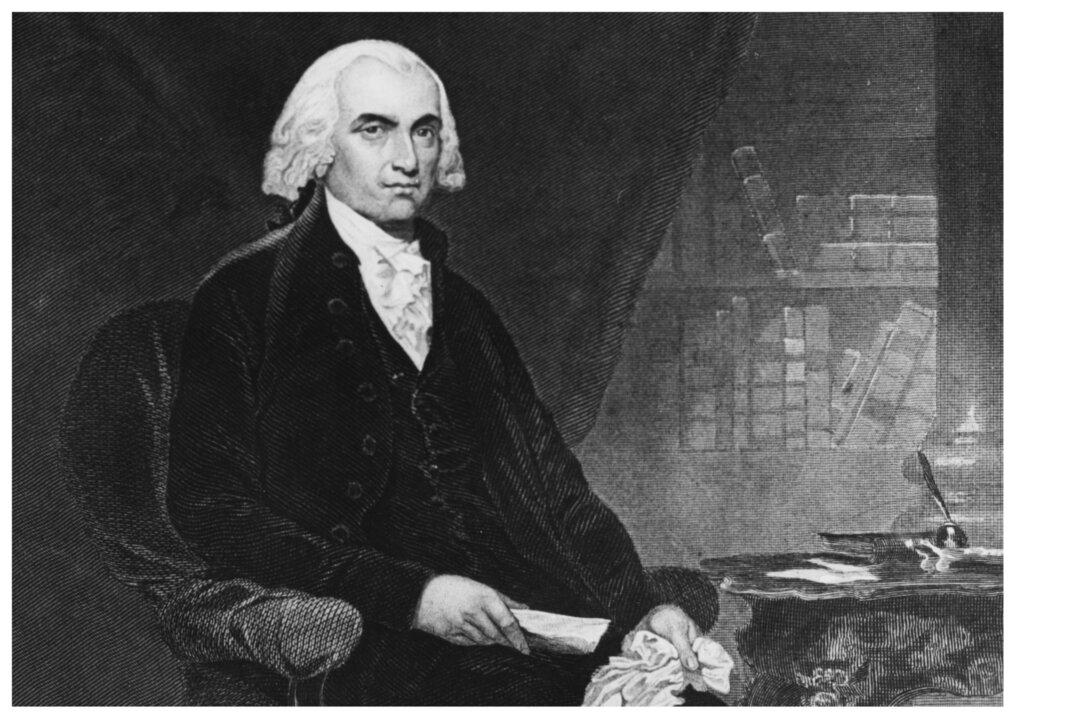

At first glance, James Madison (1751–1836) appeared unimpressive. A second glance would likely produce the same result.

He was often plagued by ill health, including what were then known as bilious fevers and a mild form of possible epilepsy. His frailty prevented him from serving in the Continental Army, and years later, as president, he exchanged the muggy summer heat of Washington for the curative airs of Montpelier, his family home in central Virginia. Though he lived to 85, considered then and now a ripe old age, the principal framer of our Constitution himself suffered from a “poor constitution,” as his contemporaries might say.