TAIPEI, Taiwan—Anyone who speaks Mandarin Chinese will end up using at least one of the words invented by cultural giant Lin Yutang. Lin Yutang’s mountain home gives sometimes playful revelation to the inner life of the man who is said to have done more than anyone else to bring China to the West.

Of his own design, Lin Yutang set his home near Yangming mountain, a natural reserve at the outskirts of Taipei city. His tomb now lies there, just below the balcony of his former living room which is now a café.

The house is a pleasant blend of Chinese and Spanish architecture; a courtyard with Spanish style columns and a Chinese style pond, rocks and bamboo. Lin was said to have gone to great care to get the right arrangement of rocks, bamboos, ferns and fish, and would often spend hours by the pond, watching them and musing to himself.

Locals and foreign visitors alike now wander through the old house, which has been kept almost just as he left it thirty years ago. The gardener, Wang Jinmu, is also an original. Now 72, he continues to climb trees and saw off wayward branches. He also still smokes, which Lin would have been very pleased with.

A visitor becomes immediately aware of the smoking habit when entering Lin’s bedroom—there is only a single bed. In his later years, he and his wife slept separately. This was not, to be sure, the result of any marital discord, but only because of Lin’s insatiable appetite for nicotine, and his abrupt, midnight awakenings that would see him snatch up a pen and pad and scrawl down his thoughts, or jokes, while puffing a hefty pipe.

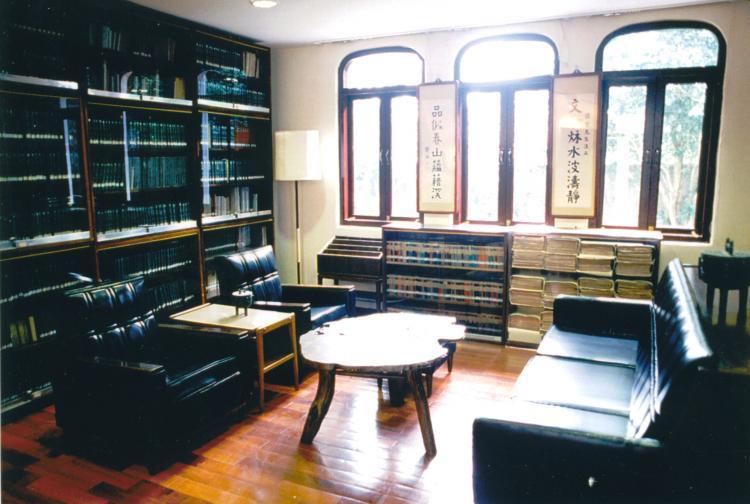

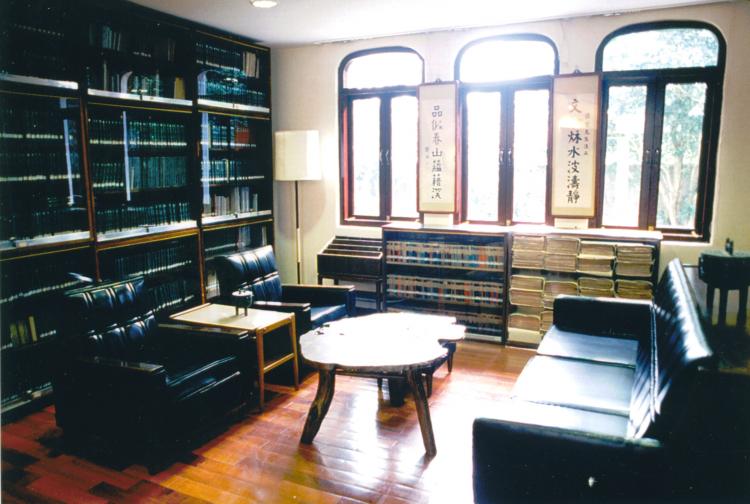

Lin was an infamous and inveterate consumer of tobacco, right up to his death. The lounging area contains relics of his habit: incased now in glass is his pipe collection, tobacco tins, and ashtrays. An ashtray takes a prominent spot on his desk, too, which he later used for peanuts, candy, and dried beef. It is said that he would often recline on his leather chair, open up the second drawer of his desk for his feet, and eat a sweet while smoking and contemplating ideas for his books or inventions.

While less famous for the latter, his inventions, particularly that of the Chinese typewriter, had a great impact on his life. Glass cabinets in his study display pictures, drafts, newspaper clippings and a model of this invention.

His idea for the typewriter obsessed Lin for decades. He found himself nearly bankrupt after he invested more $100,000 and countless hours into the project. He finished it, finally, in 1946. To bring it to fruition Lin had to invent a completely new way of categorizing Chinese characters, as making a typewriter using the traditional method—of using either ‘radicals’ (the set of fixed, small components that make up characters), or stroke order—would have been impossible.

In the end the patent was never put to commercial production. Completed during the Chinese civil war, uncertain times prevented the invention from finding a market.

An anecdote by his son sums up Lin’s approach to the project. They were sitting in a taxi and Lin was playing with a cardboard mockup of the keyboard. He commented that the crux of the problem was in there, and that the technical issues were largely trivial. His son asked whether there was, in the end, any need to go to all the trouble of building the model. After a pause, Lin whispered back, “I suppose I could have… but I couldn’t help myself. I had to make a real typewriter. I never dreamed it would cost so much.”

While the dogged pursuit for his typewriter is one of Lin’s most well-known eccentricities, it is not, by far, the only one. In the corner of the bedroom hangs a custom-made one-piece Chinese suit. A nearby note reads: “The most agreeable outfit for the Master was a Chinese long gown with a pair of Western style leather shoes. He disliked the Western suits, which he thought were so binding and inhuman.”

Deeply in debt after the typewriter project, Lin and his wife emigrated to France where he once more wrote for a living. Over his thirty-year career as an author, Lin published dozens of books, several of them going straight to the top of the bestseller lists in the mainstream Western press. Countless readers digested commentary on the Chinese psyche, philosophy and lifestyle, with reflections on his extensive experiences in the West.

Collection Representative at Lin Yutang House, Chen Yi-yen, in a telephone interview with The Epoch Times, explained some of Lin’s appeal: “His English is clear, playful and humorous. His works are great for Taiwanese people to study English, for example, because his English was excellent, his meaning is always clear, and readers will not run into difficulties of understanding.”

Lin Yutang was not only a writer, but a philosopher, an artist, a linguist, an inventor. He was also very down to earth. As a Christian, Lin used to say “If there’s anything in the human world we should pay extra special attention to, it’s not religion, nor is it learning, but eating!” This simple blend of philosophy and wit, Chen says, is a classic example of Lin Yutang’s character.

If that brings a smile to your face, think of the Chinese word for humor, Lin’s transliteration pronounced you mo (幽默), which is still used today.