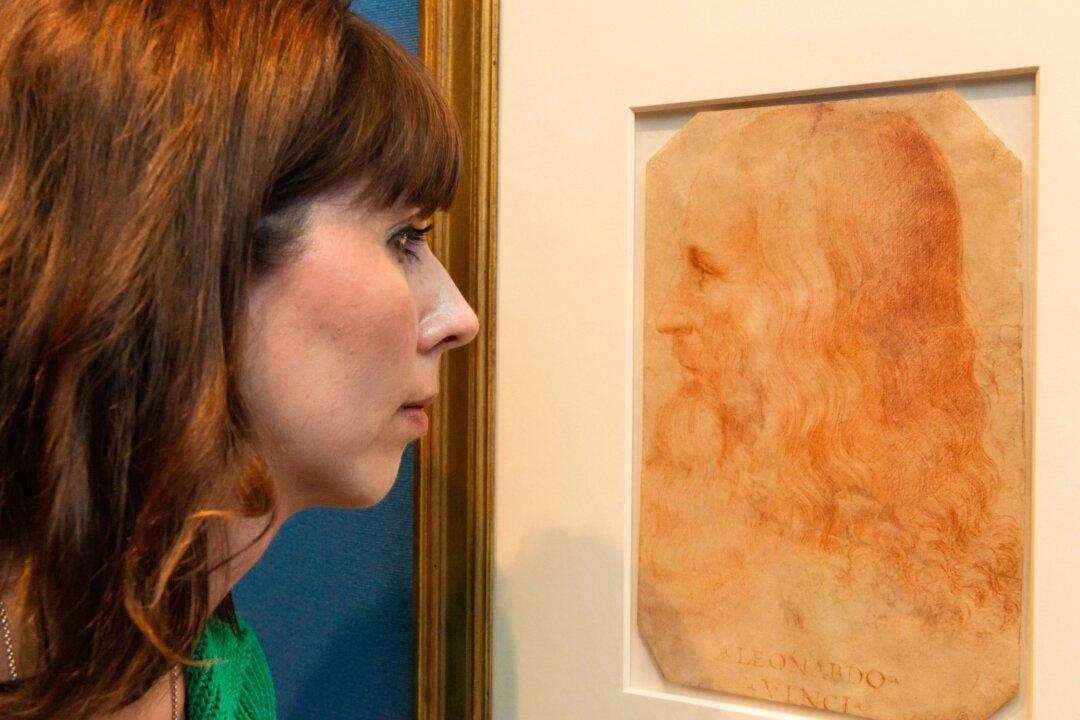

The art world is in overdrive with events to mark the 500 years since the death of the original “Renaissance man,” Leonardo da Vinci.

One exceptional exhibition, “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing,” contains over 200 works from the unrivaled collection of Leonardo’s drawings held by the British Royal Collection Trust. The exhibition is on display through Oct. 13, 2019, in The Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, in London.