A few years ago, I flew to Florence, Italy, for a friend’s wedding. Not only was I fortunate in seeing my dear friend marry in one of the city’s oldest churches, but I experienced a whole host of hearty Italian wedding traditions, hospitality, and more.

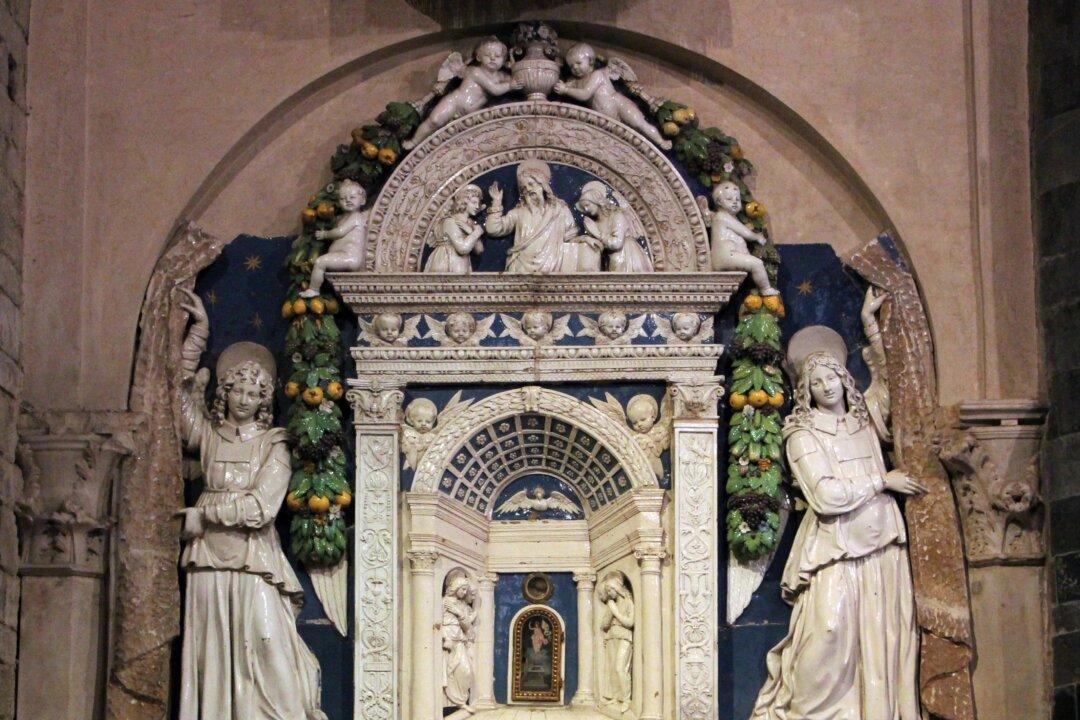

You’ll have to wait for an article on Italian wedding traditions. In this article, I want to share my surprise and delight at the sacred art in the church.