LONDON—Anyone who has played charades knows how hard it is to convey an idea without words. An artist’s challenge is to convey a moving narrative without words on a two-dimensional surface. Masters such as Italian Renaissance artist Raphael appeared to achieve this effortlessly. The foundation of these artists’ skills lies hidden behind the scenes in the mountain of drawings they made. These drawings are the DNA of great works, the building blocks of artistic mastery.

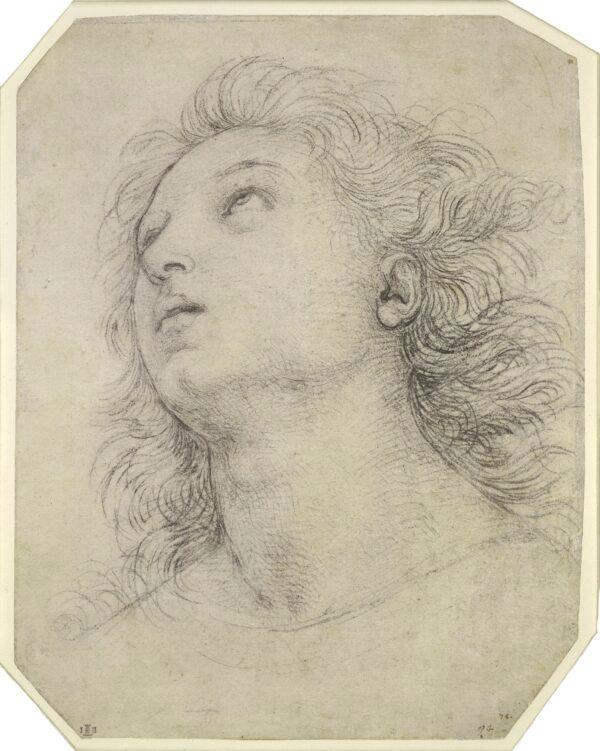

"Study for the Head of St. James," circa 1502–3, by Raphael. Black chalk, with traces of pounced underdrawing; 10 3/4 inches by 8 1/2 inches. The British Museum, London. The Trustees of The British Museum