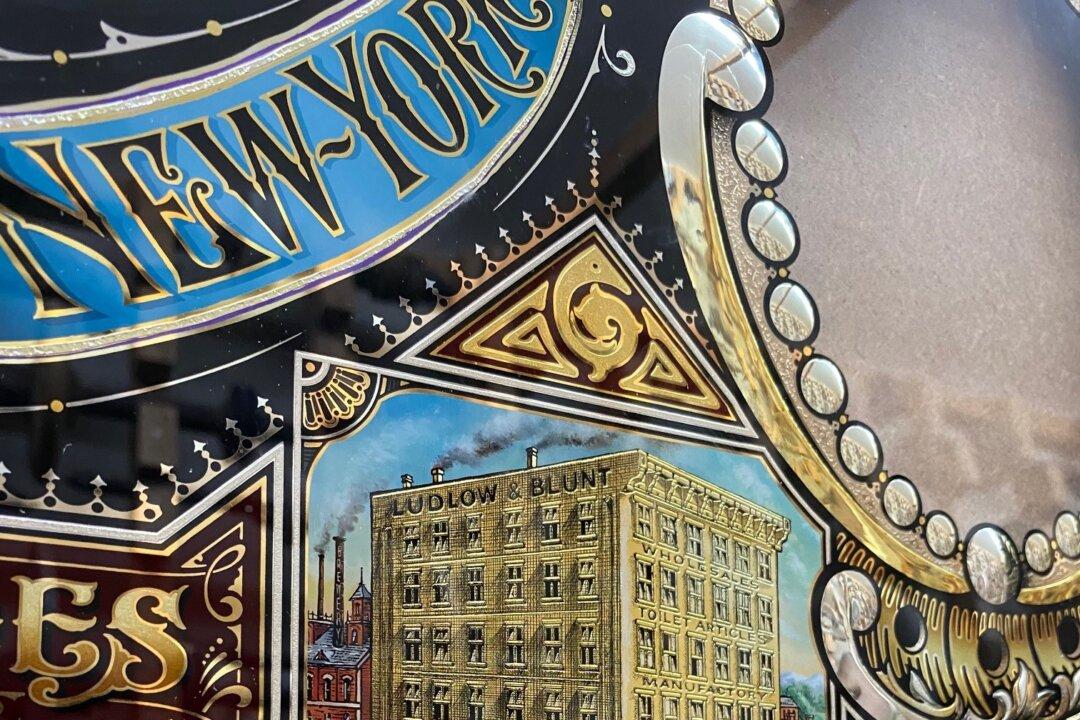

From the late 19th century through to around the 1940s, everyday shopkeepers across England advertised their businesses on glass. Across the country, rows of glass storefronts would’ve glistened along the town’s main shopping street.

Most of the store windows were “gilded or chemically silvered. It was just a beautiful thing. It would catch your eye as you walked past. They would even position these glass pieces … at a slight angle so that the consumer would be looking up into the work, into the actual name,” said traditional ornamental glass artist David Adrian Smith in a phone interview.