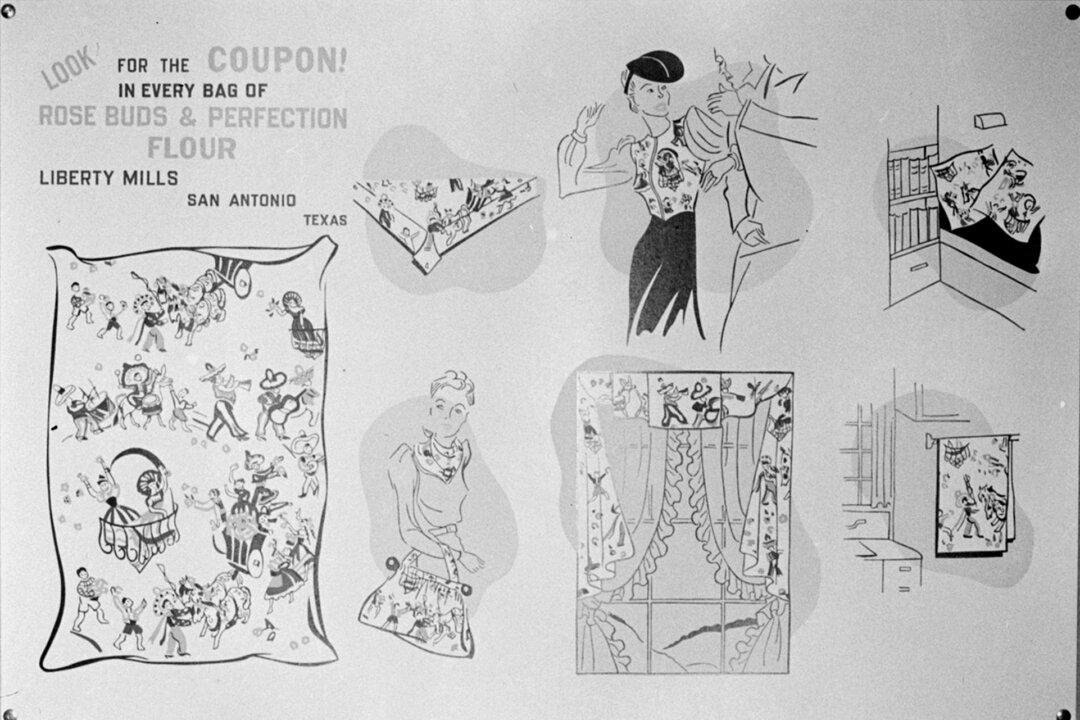

Farm and dry goods—such as oats, chicken feed, agricultural seed, flour, sugar, cornmeal, salt, dried beans, etc.—were typically bagged in generically-named feedsacks from the late 1800s through the 1950s. These feedsacks were sometimes called “chicken linen,” a country twist name that combined a common feedsacked product, chicken feed, with a generic household term, linen. During this time, people used chicken linen as a source of fabric to make clothing, bedding, curtains—anything they could imagine.

Chicken linen was the result of changing technology merging with historical trends. The homely practice of using what you had on hand still sparks memories. For example, knowing the skill and work that went into old quilts, many pieced with chicken linen, I cannot resist them.