Benjamin Franklin was so busy as an inventor, publisher, scientist, diplomat, and U.S. Founding Father that it’s easy to lose track of his other accomplishments.

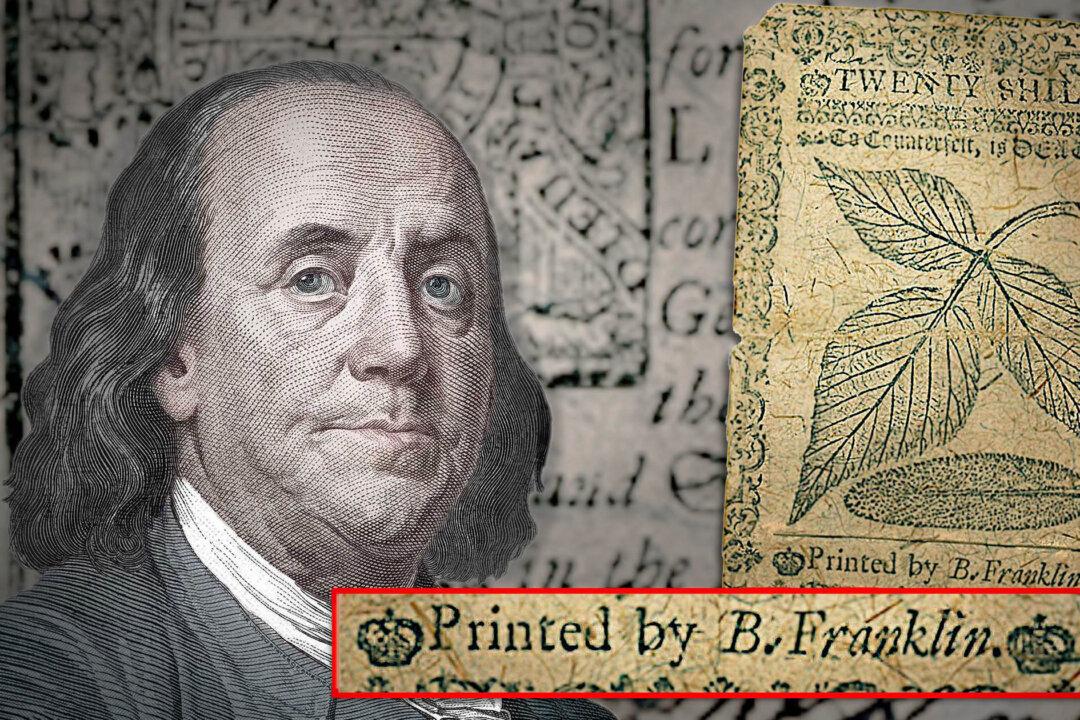

So add one more to the roster: his early work in printing colonial paper currency designed to counter the constant threat of counterfeiting.