For honest, successful entrepreneurs, the fabled journey from rags to riches is peppered with initiative, misfortune, reward, luck (good and bad), and lessons galore. In the remarkable life of the late Samuel Klein, all those elements were present in such superabundance as to render his true story almost unbelievable. It is certainly one of the most incredible I have ever run across, and it involves two of my very favorite countries as well.

How a Polish Entrepreneur Went from Death Row in a Nazi Concentration Camp to ‘the Sam Walton of Brazil’

Samuel Klein's amazing journey is a true rags to riches story

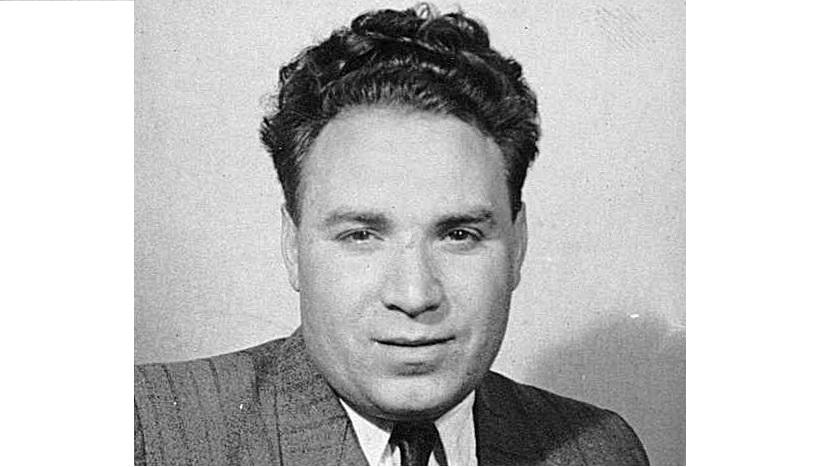

Samuel Klein in 1952. Public domain

|Updated: