Sipping more coffee these days? Laboring at home and traveling less, I find myself more frequently appreciating a good brew, as well as an invention that is to coffee what the slicing machine is to bread. I’m referring not to a burr grinder or a French press or a Keurig machine, but to the lowly paper filter invented just 112 years ago.

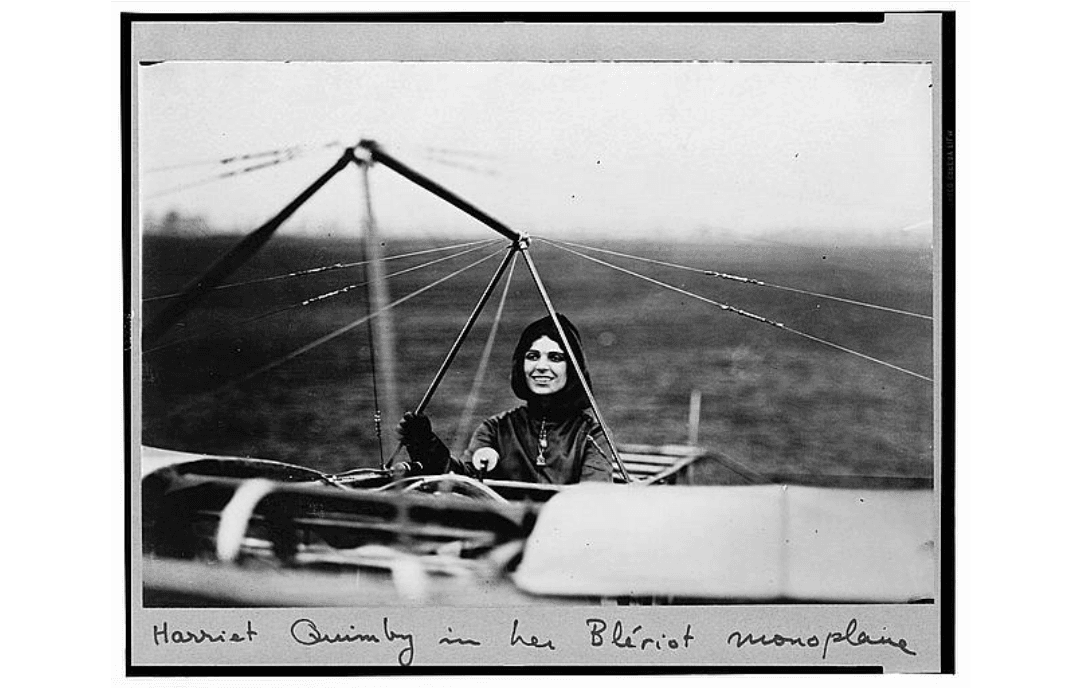

More on the filter and its female inventor in a moment. First, some interesting coffee facts I learned from personal experience or during research for this article.