NEW YORK—The mark of a great civilization is best and most completely left by its artistic achievements. This is what conductor Gerard Schwarz firmly believes, and something that has guided his actions over the course of his career.

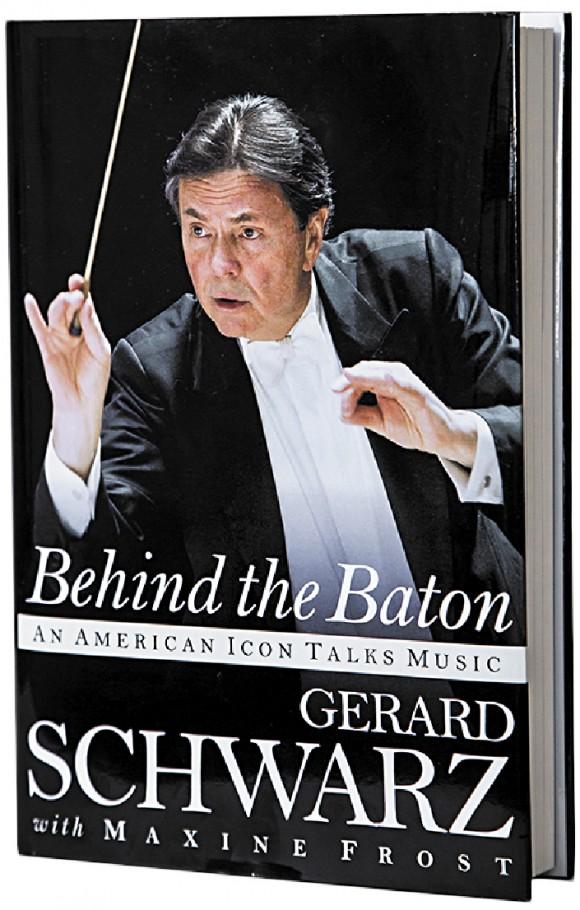

“Culture is important to civilization: If you look at every advanced society through history, they’re always known for their contribution to the arts, whether it be literature or music or philosophy or painting. If you’re known for your wars, what a shame,” said Schwarz, who will celebrate his 70th birthday this year. To commemorate this, he’s recently released a memoir (”Behind the Baton: An American Icon Talks Music“) and will release a 30-CD box set of favorite recordings with Naxos Records in the fall.

His achievements are usually given out as a long string of numbers—five Emmys, 14 Grammy nominations, six American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers awards, 300 world premieres, and 350 or so recordings. During Schwarz’s time as music director, the Seattle Symphony’s subscriber base grew from 5,000 to 35,000 and its audience numbers tripled from 100,000 to over 320,000. These numbers, while impressive, belie his personal and anecdotal approach to musical life.