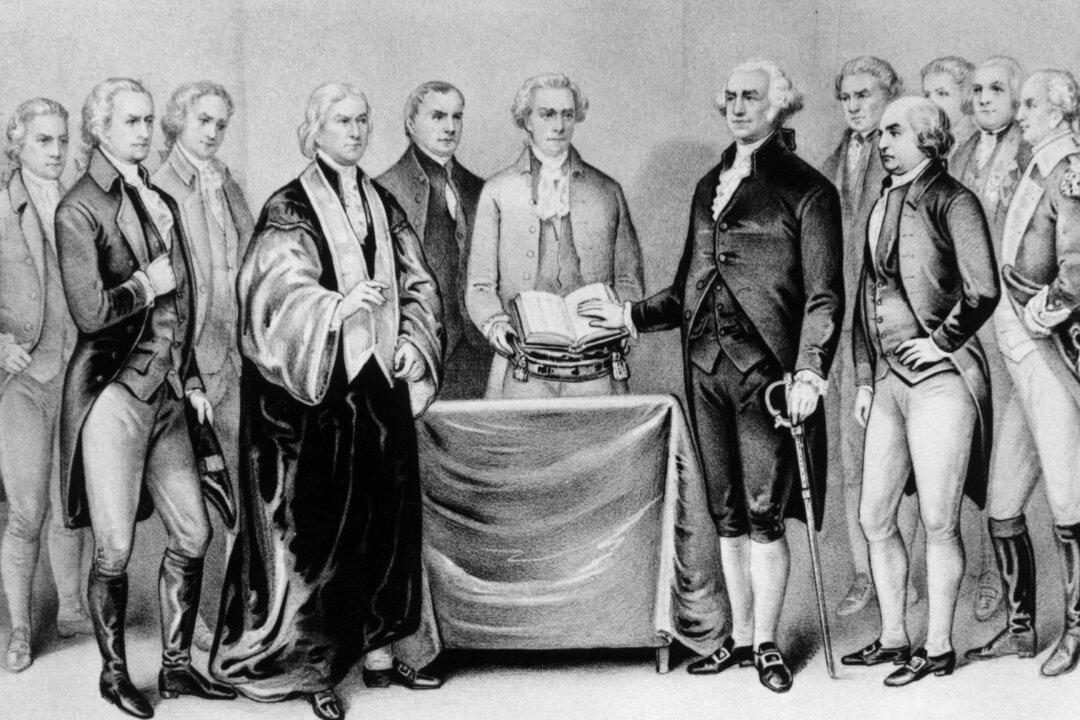

George Washington, universally acclaimed nowadays as one of our best presidents, encountered a little bad press in his own day. Even before his inauguration, he knew that facing impossibly high expectations would be a challenge during his time as president.

“My movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.” These were the unenthusiastic words of George Washington, written to fellow Revolutionary War veteran Henry Knox on April 1, 1789, not long before his nearly inevitable election as president.