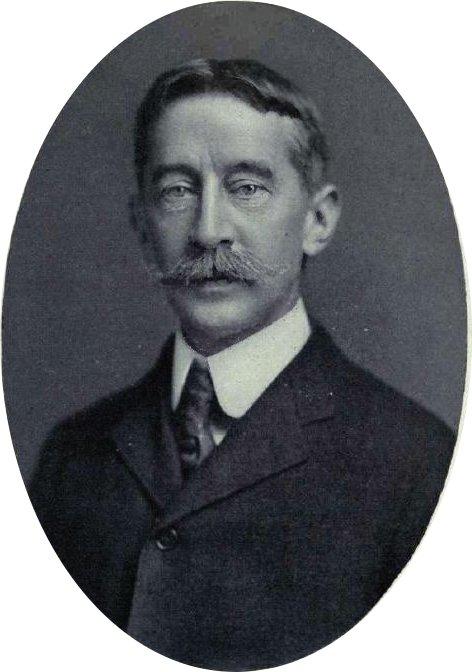

The parents of George Bird Grinnell (1849–1938) must have had great intuition when they gave him his middle name. Grinnell would become the father of American conservation with a particular affinity for ornithology―the study of birds.

"Diary of the Washburn Expedition to the Yellowstone and Firehole Rivers in the Year 1870" (1905). Public Domain