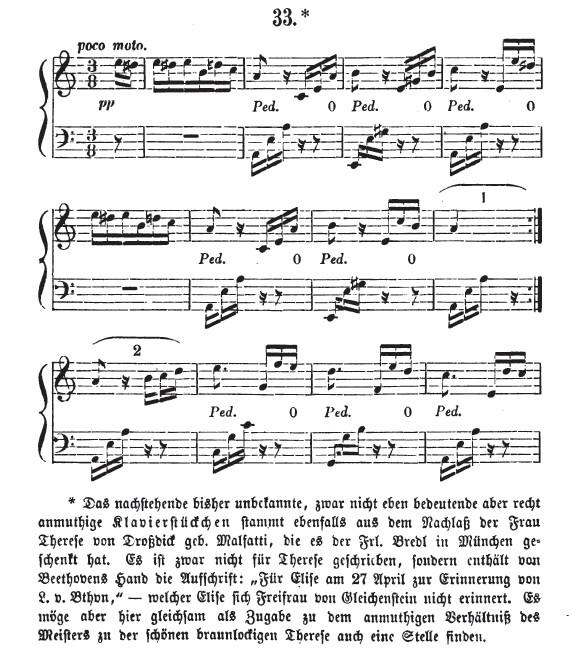

Beethoven's musical score for "Für Elise." Public Domain

I am about to put the lid down on the piano keyboard in my 6th-grade music class when a particularly animated student runs up to me and says excitedly, “Teacher, I can play ‘Für Elise’!” I encourage her to do so, but the result is just the famous first four notes, an E and the D-sharp below it, repeated, played back and forth in endless seesaw.