“My only ambition has been to engrave my name at the feet of great men and in the service of grand ideas,” wrote Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi.

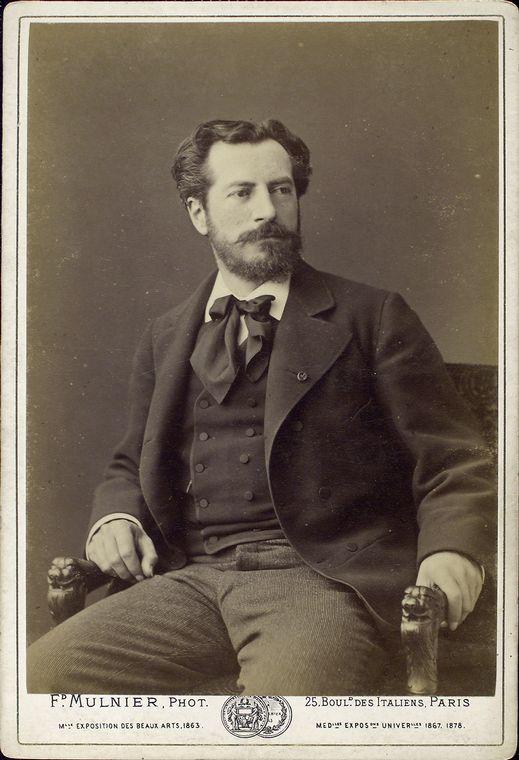

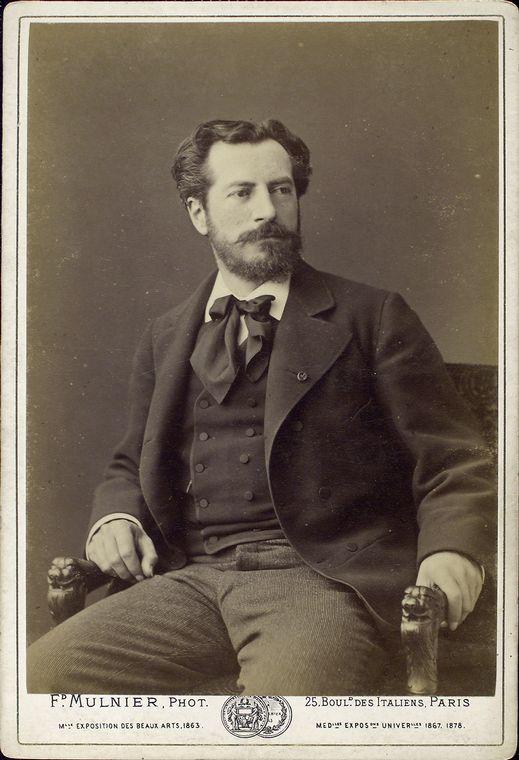

French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi circa 1880. New York Public Library Archives. Public Domain

“My only ambition has been to engrave my name at the feet of great men and in the service of grand ideas,” wrote Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi.