Trump Announces 25 Percent Tariffs on Foreign Cars

The auto tariff will take effect on April 2, when the United States will impose broad reciprocal tariffs on its trading partners.

Antidepressants Are Having Horrific Effects on Sexual Function: Dr. Josef Witt-Doerring

Dr. Josef Witt-Doerring treats patients suffering from post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD), and protracted withdrawal.

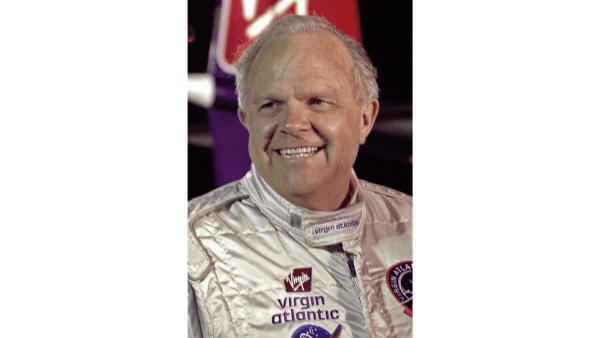

Steve Fossett: ‘The Adventurer’s Adventurer’

In this installment of ‘Profiles in History,’ we meet a commodities broker whose love of adventure established him as the greatest world-record holder.

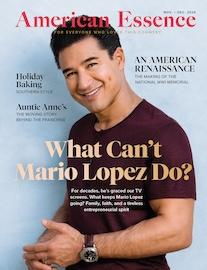

‘Bob Trevino Likes It’: A Heartwarming Tale of Surrogate Fatherhood

‘Bob Trevino Likes It’ reminds us that valuable human relationships can occur randomly and that spiritual connections can be far more powerful than bloodlines.

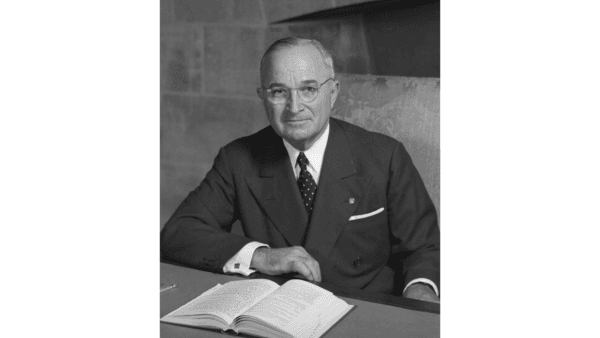

Ex Libris: Harry Truman

In this installment of our ‘Ex Libris’ series, we look at the books that influenced the last US president who guided the country through post-WWII changes.

Most Read

Top Stories

Appeals Court Allows Block on Trump Admin’s Deportation Proclamation

Judge Justin Walker dissented from the decision.

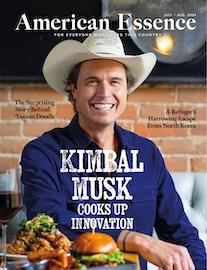

Musk Tapped to Help Probe Signal Chat Leak Involving Journalist

The investigation seeks to uncover how The Atlantic’s editor accessed a sensitive Signal chat with top U.S. security officials.

Intelligence Leaders Grilled by Democrats Over Handling of Military Information on Signal Chat

Gabbard suggested that the chat was merely a policy discussion rather than a meaningful insight into U.S. military operations.

Reported Arrests of China’s Top Military Brass Indicate Political Crisis, Experts Say

Some analysts have said that the purge suggests that political infighting within the communist regime has intensified.

A Look at Trump’s Tariff Plan to Revive the US Auto Industry

Tariffs are a component in the toolkit Trump is using to achieve his goal of restoring domestic manufacturing, experts say.

Why Do Some People Remember Their Dreams While Others Forget?

Research is uncovering why we dream, who remembers them best, and how to improve recall.

Communist China Still One of the Worst Abusers of Religious Freedom, Report Says

‘The CCP persecution of people of faith reveals a regime that denies the dignity of the individual,’ Rep. John Moolenaar said.

Day in Photos: Migrants in the English Channel, Fishermen’s Protest in Chile, and Blooming Magnolias in Austria

A look into the world through the lens of photography.

DOGE Says 315,000 Credit Cards Have Been Canceled, Limited by Federal Agencies

Last month, DOGE said that more than 4.6 million credit cards were used across federal agencies last year.

NPR, PBS Chiefs Respond to GOP Allegations of Bias in House Hearing

The hearing comes a day after President Donald Trump said that NPR and PBS should be defunded.

Georgia Senate Votes to Ban Cellphones in Elementary, Middle Schools

Arkansas, California, Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Minnesota, Ohio, South Carolina, and Virginia have enacted similar measures.

▶Shen Yun is a Reminder of ‘How Much Good’ There Is in the World

Shen Yun Performing Arts brought the rich cultural heritage of ancient China to life at a sold-out performance at the State Theatre New Jersey in New Brunswick.

Almost 10 Million Student Loan Borrowers at Risk of Significant Credit Score Drops, Fed Warns

The damage will remain on their credit reports for seven years, said experts at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Trump Admin Asks Supreme Court to Let It Block Education Grants Over DEI Concerns

A district court stopped the administration’s plan to cancel grants related to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Tracking Trump’s High Level Appointments, Senate Confirmations

The Senate is undertaking the confirmation process for the president’s new administration.

Brazil’s Supreme Court to Try Bolsonaro Over Alleged Coup Plot

Brazil’s top court has agreed to try former President Jair Bolsonaro and key allies over an alleged post-election coup scheme.

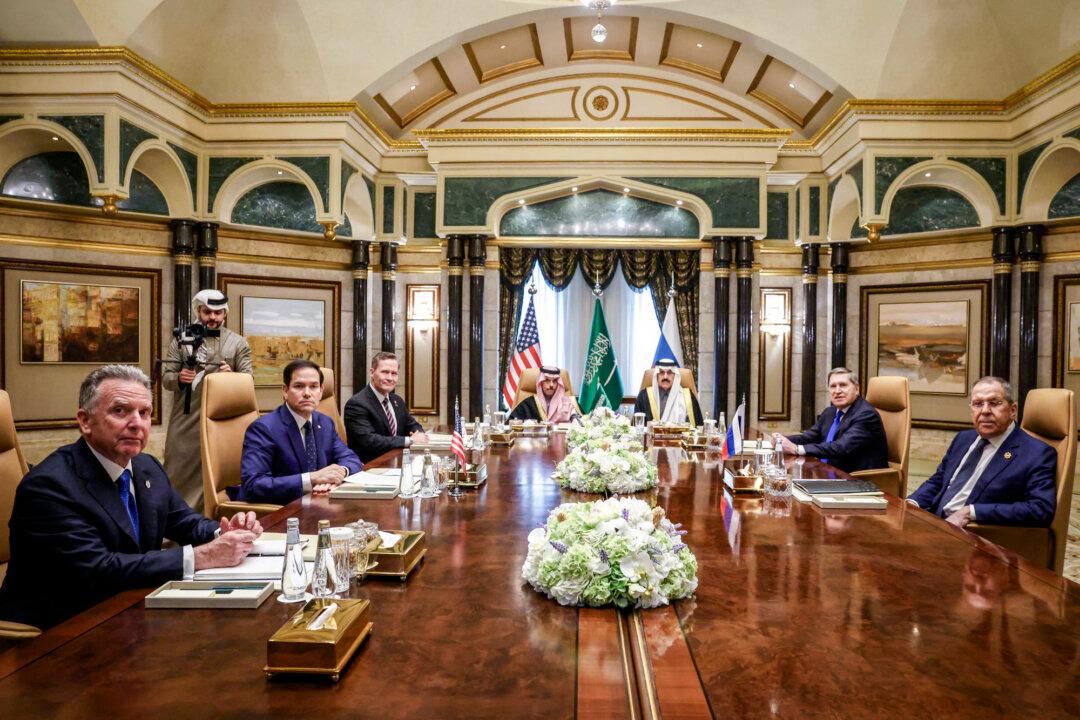

Russian Negotiators May Be ‘Dragging Their Feet’ in Ukraine Cease-Fire Talks, Trump Says

The Trump administration has negotiated a limited cease-fire covering Russia and Ukraine’s energy sites, but a broader truce is still in the works.

NATO Secretary General Says 4 Missing US Soldiers in Lithuania Have Died

The U.S. Army has only confirmed the disappearance of the soldiers during a training session near the Belarusian border earlier in the day.

EU Rejects Russian Demand to Lift Sanctions as Condition for Black Sea Cease-Fire

Zelenskyy said Russia, not Ukraine, was holding up progress on a broader cease-fire.

Homeland Security Secretary Confirms Plans to Eliminate FEMA

Trump has signaled that he wants to either eliminate or overhaul the agency.

Dollar Tree Announces Sale of Family Dollar Subsidiary for $1 Billion

Dollar Tree shares have tanked by more than 44 percent over the past year.

Belvoir Castle: A Gothic Revival Masterpiece

In this installment of ‘Larger Than Life: Architecture Through the Ages,’ we visit a faux historic castle in Leicestershire, England.

Special Coverage

Special Coverage

![[LIVE Q&A 03/27 at 10:30AM ET] Trump Mandates Proof of Citizenship for Elections | Live With Josh](https://www.theepochtimes.com/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimg.theepochtimes.com%2Fassets%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F03%2F26%2Fid5831915-032725_REC-600x338.jpg&w=1200&q=75)