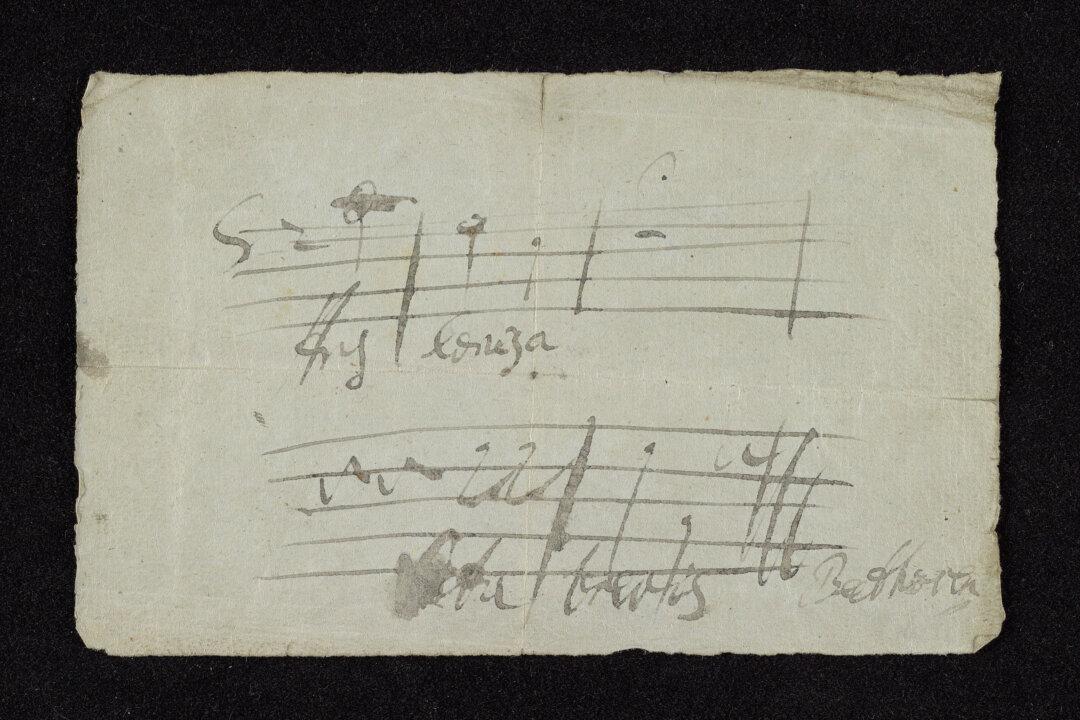

When Ludwig van Beethoven penned his manuscripts, he transformed black ink and white paper into something beyond the ordinary. In 1907, J.P. Morgan experienced this special quality when he came across one of the maestro’s original manuscripts.

Morgan had been doing business in Paris when he heard about a dealer living in Florence, Italy, who had held a concert playing from Beethoven’s original manuscript for Violin and Piano Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96.