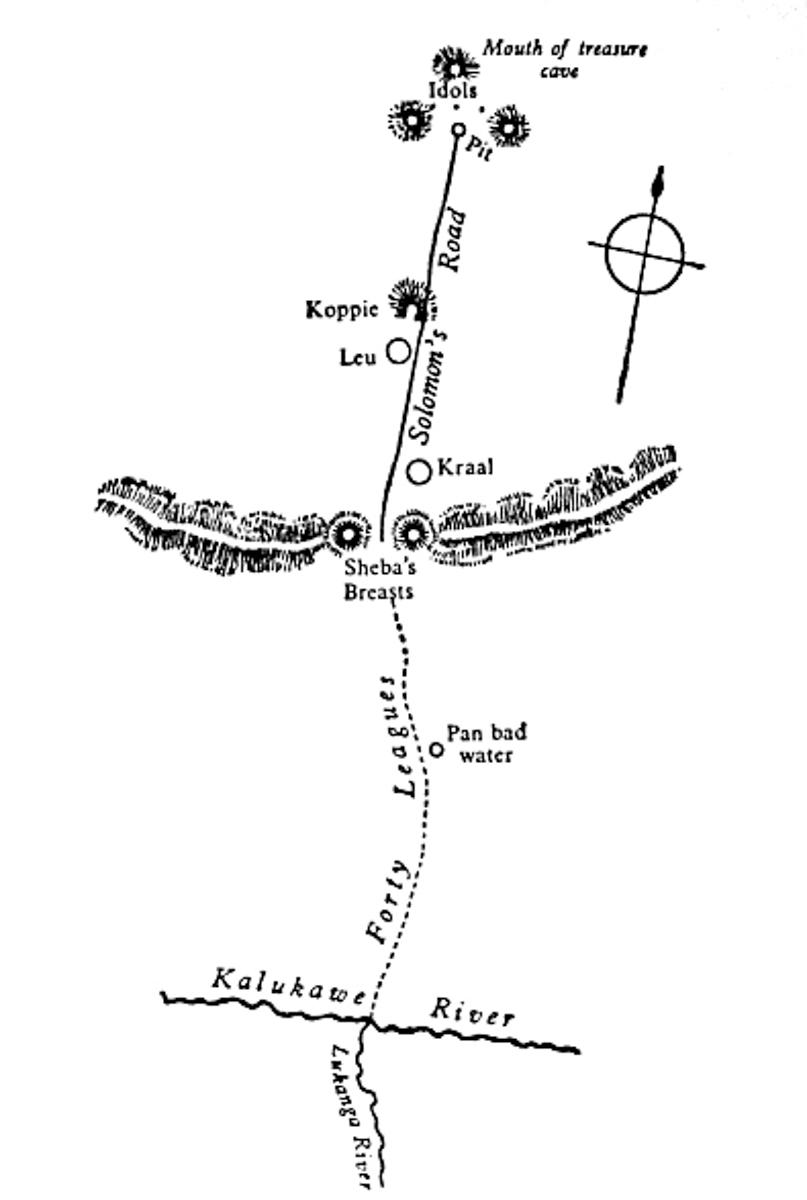

When was the last time you read a book that got you started with a tattered map scratched out in blood? And imagine if that map led you on a perilous journey where scraps of an ominous legend brought you to a stony vault, which in turn descended to a lost treasure chamber, where presiding over an ancient table loomed a colossal skeletal figure of Death in all his grim glory, brandishing a spear.

A treasure map leading to Kukuanaland, in "King Solomon's Mines," one of the most popular English novels of the 19th century. PD-US