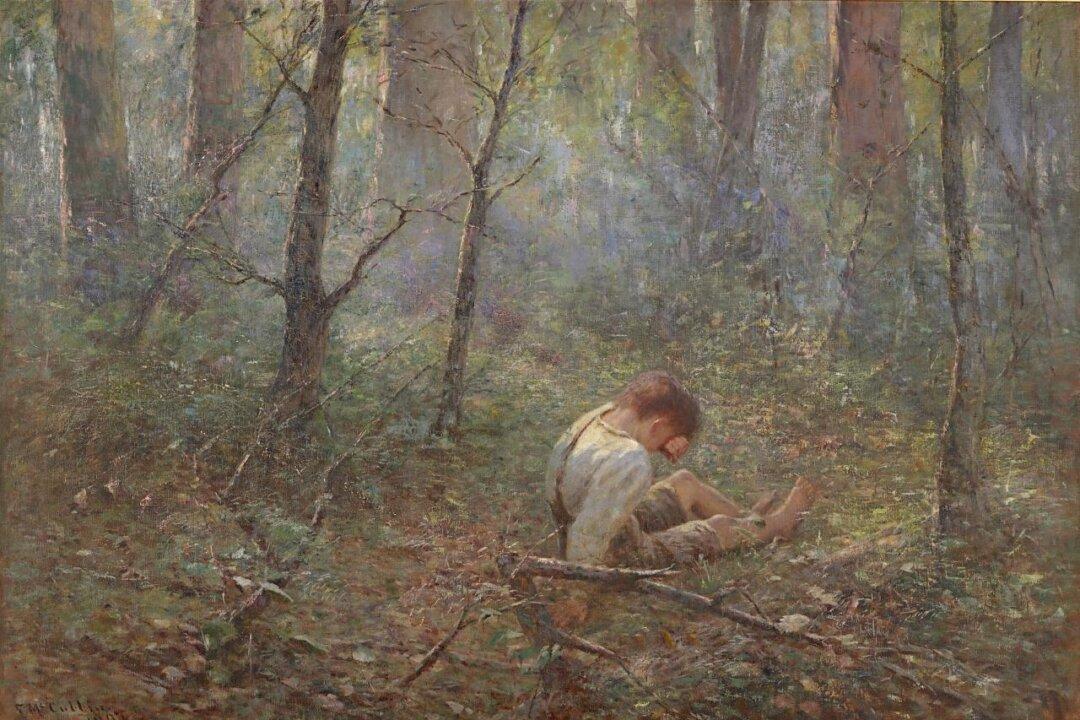

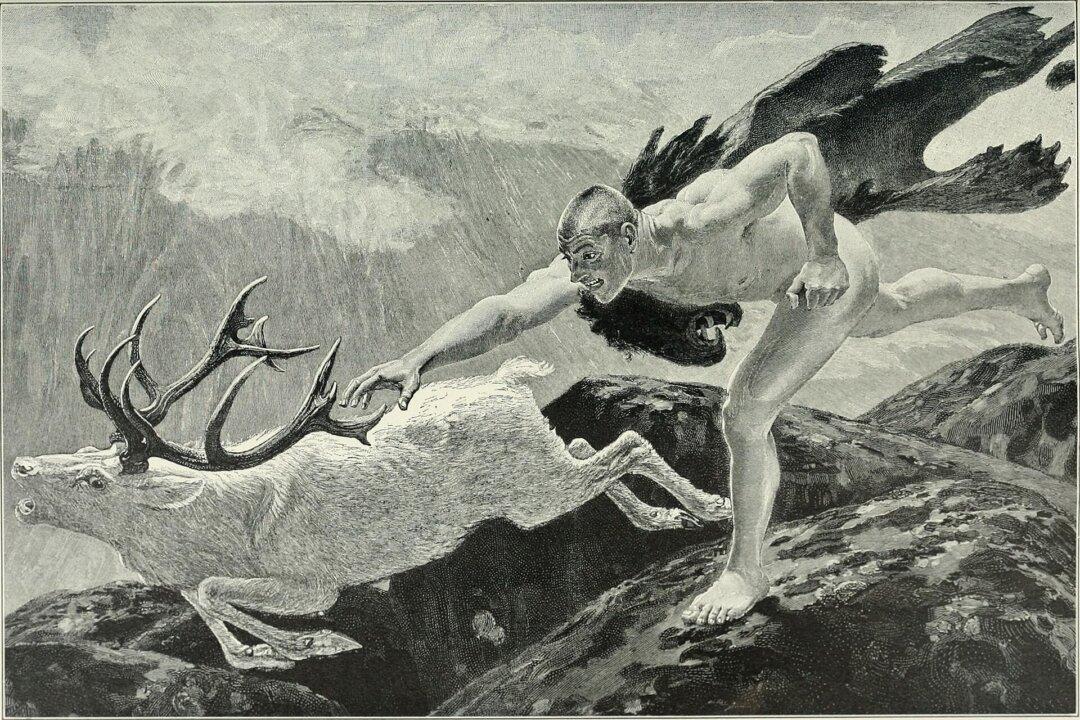

Imagine that you were lost in a wilderness and had to find your way out. Fortunately, you have with you a number of things, or tools, if you will. In the first instance you have a kit bag, which is itself useful. In it are various articles: a bottle of water, a knife, fork, and spoon, a map, lighter fuel, matches, a compass, a chocolate bar, some rope, scissors, a can opener, a wrap-up plastic raincoat, and a few more pieces too, like the watch on your wrist.

The question I would ask you is simply this: Would you, therefore, given that you are lost and are not sure where or how far the next safe port of call is, jettison any of these items or tools? Would you say, this item is irrelevant, and I don’t need it—I’ll never need it—get rid of it? And further, when you are safely back home and start writing of your experiences, will you be prescribing to other travelers in the wilderness: You must never take a bottle of water with you—it’s stupid, it’s cheating, it’s pointless? Or, argue that having a map with you means that you are not really lost, so you are not really making a journey?