Certain musical works speak of their time in a timeless fashion. Think of the heady Romanticism of Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique,” or the naive musical picture-making of Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” concertos. Then there are compositions that seem to translate human feeling directly into musical language, works in which time itself falls away. Chopin’s Preludes, Op. 28, belong to the latter category.

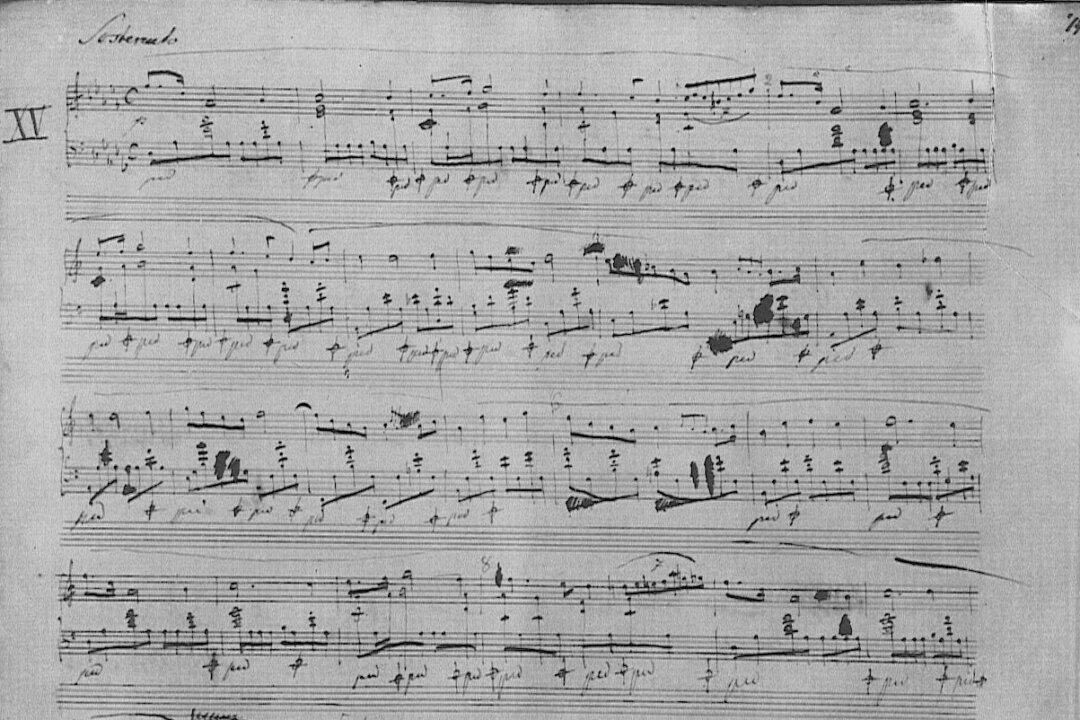

Frédéric François Chopin arrived on the Western art music scene at precisely the right time for an artist of his gifts and temperament. The piano was only a century old when he was born in 1810 in Poland to a French father and a Polish mother, and the instrument’s expressive potential was only beginning to be comprehended. His parents arranged for piano lessons early, and by age 8, young Frédéric was giving concerts and composing his own pieces. He learned no other instrument and needed no other musical outlet. Alone among major composers, everything Chopin composed would include the piano in its scoring, from two piano concertos to a cello-piano sonata to 17 songs for voice and piano, and of course, dozens and dozens of solo piano pieces, among them mazurkas, waltzes, polonaises, études, nocturnes, ballades—and preludes.