New evidence has emerged of organ harvesting still occurring in China, this time from a South Korean television documentary, despite Chinese official pronouncement that such abuses have ended.

A program called “Investigative Report 7,” broadcast on TV Chosun, a cable network owned by one of South Korea’s largest newspapers, Chosun Ilbo, went undercover to probe the phenomenon of South Korean medical tourists traveling to China for organ transplant surgery. The segment aired in South Korea on Nov. 15.

The program’s crew traveled to a hospital in Tianjin City, northeastern China, under the pretense that they were inquiring about surgery for a South Korean patient with kidney disease in need of a transplant.

The reporter, with a secret camera, filmed his interactions with the hospital staff, who informed him that a matching organ can be found within weeks. If the patient’s family is willing to donate additional money to the hospital’s charity, the waiting period can be sped up and the patient can be assigned to a matching organ sooner, a nurse told the reporter. The documentary did not specify precisely when the incidents took place, though it appears to have been earlier this year.

Where could the organs, which seem to be readily available at request, be coming from?

Based on The Epoch Times’ own award-winning, extensive reportage on organ harvesting in the past, one of the major sources is likely from prisoners of conscience who are held inside China’s prisons for their faith. This includes principally practitioners of Falun Gong, a spiritual practice that the Chinese regime has banned and severely persecuted since 1999. The organs are likely forcibly taken from their bodies, causing their death in the process.

Other target groups for organ harvesting include Uyghur Muslims, who have been subjected to widespread blood testing and DNA-typing, as well as individuals who are simply kidnapped off the streets in China.

Footage of surgery rooms within the Tianjin First Central Hospital, captured on the South Korean documentary. Screenshot via YouTube

The Chinese regime has consistently claimed that the organs come from executed prisoners. But the number of organ transplants performed far exceeds the number of executions, which has dropped significantly in recent years. The official explanation is far from sufficient for accounting for the level of observable transplant activity, particularly considering that the country’s voluntary organ donor system is minimal. According to traditional Chinese beliefs, disturbing a person’s corpse after death is taboo.

The documentary also notes these discrepancies, citing previous reports by independent researchers—and arrives at the same conclusions about the likelihood of an organ bank with prisoners being killed on order for transplant surgery.

But the program is rare, concrete evidence—directly from Chinese hospital staff and South Korean doctors—that organ harvesting continues unabated today, fueled in part by foreigners desperate to prolong their lives with transplant surgery.

Chinese officials promised that use of prisoners as an organ source would cease from January, 2015 onwards. These promises, and subsequent claims of reform, led to high-profile endorsement of China’s transplant system from the World Health Organization and The Transplantation Society. The Korean investigative report appears to belie such claims.

Hospital Accounts

The documentary estimates that since 2000, roughly 2,000 South Koreans travel to China for transplant surgery every year, a number significantly higher than data from a recently published study in the “Transplantation” medical journal, conducted with South Korean transplant centers that followed up with their patients who got surgery in China. The documentary does not explain how it got the figure, though it appears to be an extrapolation based from anecdotal data acquired by reporters.The crew traveled to a hospital in Tianjin known to be popular with South Korean medical tourists, but did not identify it by name. Based on the filmed images of the hospital and its description, it matches with the Tianjin First Central Hospital that The Epoch Times has previously reported about. The hospital has an entire multi-story building dedicated to organ transplantation, with, at one stage, a 500-bed capacity.

Upon arriving at the hospital, the undercover reporter was greeted by a Korean-speaking nurse who showed him around the ward. A South Korean patient who had just successfully undergone transplant surgery told the reporter she waited two months for a matching organ. The patient’s son told the reporter it took about two hours from time of organ removal to arriving at the hospital. He also said the hospital charged different prices for different groups.

The Korean-speaking nurse at Tianjin First Central Hospital, shown in the documentary. Screenshot via YouTube

The reporter asked how many transplant surgeries the hospital typically performs. The nurse replied that the day before, there were three kidney and four liver surgeries. If this were the average daily transplant volume at the hospital, it would be performing about 2,500 transplants per year. It is unclear what the actual average daily transplants at the hospital are, however.

After the nurse and a transplant doctor reviewed medical records from the purported South Korean patient and confirmed the patient was suitable for surgery, the reporter asked how long the patient would have to wait until the surgery. The nurse replied that it depends, but some patients only waited a week, two weeks, or 50 days. She then added that if one wished to expedite the process and be prioritized for an organ, one could donate money to the hospital’s charity—additional to the surgery fee. When asked how much to donate, she replied 10,000 yuan (roughly $1,500).

In a chilling exchange, the reporter asked if the purported patient could receive a young person’s organ. The nurse said the hospital only chooses organs from young people.

The nurse also showed the reporter around a ward especially for foreigners, revealing that one room—spacious and well-furnished—belonged to a Middle Eastern patient whose surgery fee was “taken care of at the consulate.”

She also informed the reporter that many patients’ relatives stay at a nearby hotel belonging to the hospital, a 16-story building.

The program crew also visited the hotel and spoke with a South Korean couple, one of whom was a transplant patient who recently completed surgery. The couple said one floor was just for Korean patients and their relatives. The couple was on a three-month visa.

Claims of Human Experiments

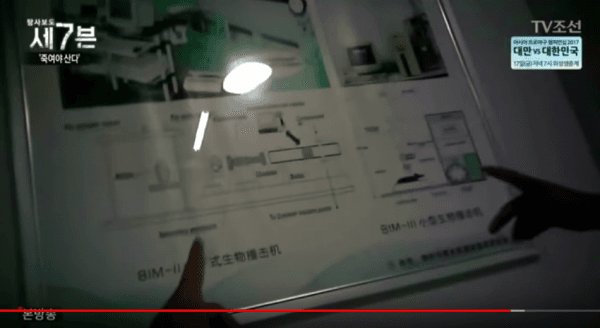

The program also examined reports that the disgraced former police chief of Chongqing, Wang Lijun, oversaw morbid human experiments to research organ transplant methods that would better preserve the organs’ condition, first documented by the nonprofit group, the World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong (WOIPFG).The documentary crew traveled to the Chongqing hospital and research lab supervised by Wang, and found blueprints hanging on the wall for a machine that would inflict brain-stem injuries that would cause brain death, looking similar to the one patented under Wang’s name found by WOIPFG. The patents for Wang Lijun’s machine are available online, identifying it as a “Primary brain stem injury impacting machine.”

Blueprints of a brain injury-inducing machine, hung up at the Chongqing hospital that Wang Lijun supervised, as shown in the documentary. Screenshot via YouTube

When the reporter asked about the machine’s purpose, the lab staff confirmed that the machine could be used on a human to render him brain dead while keeping other organs in the body healthy.

Complicit Doctors in South Korea

South Korean patients are referred to Chinese hospitals by doctors back home. The program crew visited a Seoul hospital, where the doctor admitted to recommending patients to visit the Tianjin hospital before, but that he no longer does. When asked about concerns regarding the organs’ source, the doctor refused to comment.

A doctor at an unnamed Korean hospital talks to the program's reporter. Screenshot via YouTube

At another unnamed hospital, a doctor said he knew the organs in China are from “prisoners persecuted for their faith.” The ethical dilemma prompted him to later stop recommending patients to China. When asked whether he regretted his previous decisions, he said no, as the patient needed the transplant surgery in order to live.

A request for response from the Korean Society for Transplantation went unanswered as of press time.

Concerns for South Korea

Last year, an anonymous source who identified him or herself as a former worker at the Tianjin First Central Hospital wrote in The Epoch Times about his or her experience.“Many of the foreign transplant patients came to China looking for a liver or kidney. The bulk of these foreigners were South Koreans,” read the account. The source also explained how patients were referred to the hospital. “A well-known South Korean doctor with one of the biggest hospitals in South Korea would introduce his patients to a middleman. This middleman would then refer these patients to the Tianjin hospital.”

In 2015, David Matas, one of the most prominent independent researchers who has documented evidence of organ harvesting in China, raised concerns about the lack of transparency regarding organ sourcing in China, at a medical industry conference held in Seoul, South Korea.

This past July, several international health organizations signed a letter hailing China’s “organ donation and transplantation reform,” including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences (PAS), and The Transplantation Society (TTS), reported Global Times, a Chinese state-run newspaper.

Asked whether the PAS will change its stance toward China’s system in light of the documentary, Dr. Francis Delmonico, a transplant expert and PAS Academician, did not directly address the evidence in the Korean documentary of continued abuses, responding instead: “the stance of the PAS is to support the reform of China that is consistent with the PAS Statement—and signed by Chinese colleagues at the PAS Summit.”