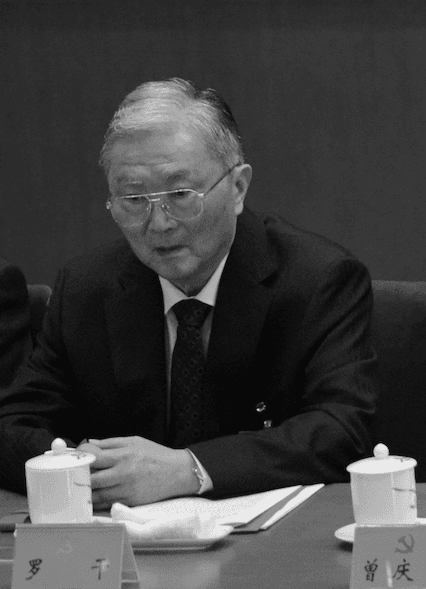

Rumors of China’s former security czar Luo Gan using his political clout to benefit his family have long been circulating on the Chinese internet.

But with the publication of a recent exposé on the shady financial dealings of Luo’s nephew, Luo Shaoyu, Luo Gan’s family’s secrets are being unveiled.

The fact that the Chinese authorities—hawk-eyed and ready to censor anything they dislike, especially when pertaining to Party members—did not take down the story also signals that Luo’s standing within the Chinese Communist Party is truly waning, despite his status as a senior cadre.

Dengshenxian, or Depth Paper, a Chinese online publication focusing on in-depth business reporting, published a story on Nov. 27 last year, detailing how Luo Shaoyu’s Chongqing-based company, Dongyin, and its subsidiaries, had amassed tens of billions of yuan (one billion yuan equals approximately $158 million) in overdue loans, spread among more than 30 banks and financial institutions.

Clouds gather over the Chongqing skyline on August 23, 2007. China Photos/Getty Images

Meanwhile, Luo and some of his family members had set up dozens of offshore companies, while sitting on the board of directors or serving as shareholders of several Hong Kong companies.

Luo Gan’s Family Business

According to Forbes’ 2017 list of wealthiest people in China, Luo Shaoyu’s family ranked 223rd with 9.25 billion (about $1.46 billion) yuan in assets.The article did not mention Luo’s connections to Luo Gan, but through examining previous media reports, The Epoch Times has confirmed Luo Shaoyu’s familial connection to the once-powerful official.

Luo Gan acquired a multi-billionyuan company through his family’s political connections.

Previous mainland and overseas Chinese reports have explained how Luo Shaoyu made use of his powerful uncle’s position to benefit his companies. In 1997, Luo and his mother established Zhongqi, a firm that manufactures armored cars and police cars.

Soon after, Luo Gan became head of the country’s security apparatus, as secretary of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission. He ensured his nephew’s company’s cars were purchased by the state.

In 1998, Luo Shaoyu set his ambitions higher. He paved the way for acquiring Jiangdong, a state-owned firm that manufactures engine parts, by first partnering with it to establish an investment holding company, Dongyin. He then gave his family company, Zhongqi, all the equity shares to Dongyin.

Several years later, in 2002, through his uncle’s connections, he successfully persuaded the Yancheng City authorities in charge of managing state-owned assets to approve Dongyin’s acquisition of Jiangdong (Jiangdong is based in Yancheng). In this way, Luo acquired a multi-billion-yuan company through his family’s political connections.

Luo Gan’s Darker Crimes

Luo Gan rose through the political ranks when Jiang Zemin was in power as top Party leader. When Jiang launched a nationwide campaign in 1999 to persecute adherents of the spiritual practice Falun Gong, Luo was instrumental in mobilizing the country’s law enforcement to track down, arrest, detain, and torture practitioners. He helped Jiang establish an extralegal Party organization similar to the Gestapo, called the 610 office, that would organize those tasks. Luo had duly demonstrated his political loyalty and was rewarded with an appointment to the Party’s most powerful decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee.Jiang and Luo saw Falun Gong’s popularity—with estimates of 70 to 100 million adherents by 1999—as a threat to the Communist Party’s control over society. Luo organized secret investigations, beginning in 1996, infiltrating parks and public spaces across the country to collect the identities and addresses of practitioners who exercised there. Falun Gong itself is known for not keeping lists of those who practice.

When Falun Gong adherents collectively planned to appeal to the central authorities on April 25, 1999 for the release of several recently arrested practitioners, it was Luo who told police to guide the gathered practitioners to line up alongside Zhongnanhai, the Party leadership’s compound in Beijing, according to Ethan Gutmann, author of “The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China’s Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem.”

Falun Gong practitioners gathered around Zhongnanhai on April 25, 1999. Photo courtesy Clearwisdom.net

The resulting images of adherents lined up ten deep on the sidewalks opposite Zhongnanhai became part of the Party’s strategy to spread false propaganda that Falun Gong practitioners wished to overthrow Party rule.

On Jan. 23, 2001, Luo staged another incident to defame practitioners. Several men and women whom Chinese state media claimed were Falun Gong practitioners appeared to have immolated themselves publicly in Tiananmen Square. Reportage by The Washington Post later revealed that one of the women was not, in fact, a practitioner. An award-winning documentary, “False Fire,” analyzed the state media footage and demonstrated discrepancies that revealed the whole thing was orchestrated to turn public opinion against the adherents.

Gutmann estimates that at any given time, 450,000 to one million practitioners are held in China’s labor camps, prison camps, and other long-term detention facilities. Thousands are estimated to have died of torture, according to the Falun Dafa Information Center, the official press office for the spiritual practice.

The 2016 investigative report, “Bloody Harvest/The Slaughter: An Update,” estimates that since 2000, hospitals in China have done between 60,000 and 100,000 organ transplants a year, with most of these organs coming from detained Falun Gong practitioners.

Courts in Spain and Argentina have since charged Jiang and Luo with genocide. The latter issued an international arrest warrant for both men.

Even after Jiang formally stepped down from his position as head of the CCP in 2002, he and his faction continued to rule from behind the curtains. After the 2012 leadership transition to Xi Jinping as head of the Communist Party, though, Xi became wary of Party members loyal to Jiang, who made up a powerful opposition. Xi launched an anti-corruption campaign to purge them.

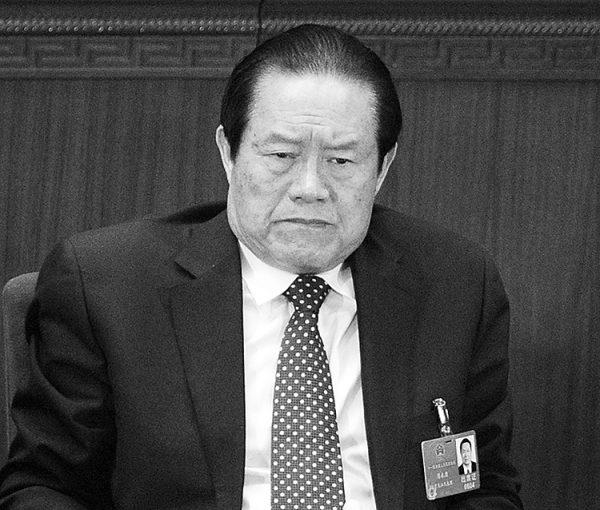

When Zhou Yongkang, Jiang faction member and successor to Luo Gan’s security czar position, was put under investigation for bribery, Chinese media reports spilled the beans on how Zhou’s and Luo’s families profited tremendously from mining deals. They once tried to take over a molybdenite mine in Luoyang City, Henan Province worth 470 billion yuan.

Before his sentence to life imprisonment for corruption, Zhou Yongkang attends the opening session of the National People's Congress on March 5, 2012. Liu Jin/AFP/Getty Images

At the 19th National Congress in October 2017, a major political meeting where Xi further consolidated power within the Party, Luo failed to show up at the opening ceremony along with other senior cadres. Rumors soon swirled that he had fallen ill, or that he was being punished for his misdeeds.

Whatever the reason may be, this latest spate of bad news about Luo’s family shows he—and the faction he belongs to—has truly fallen out of favor.

Fang Xiao contributed to this report.

Recommended Video: