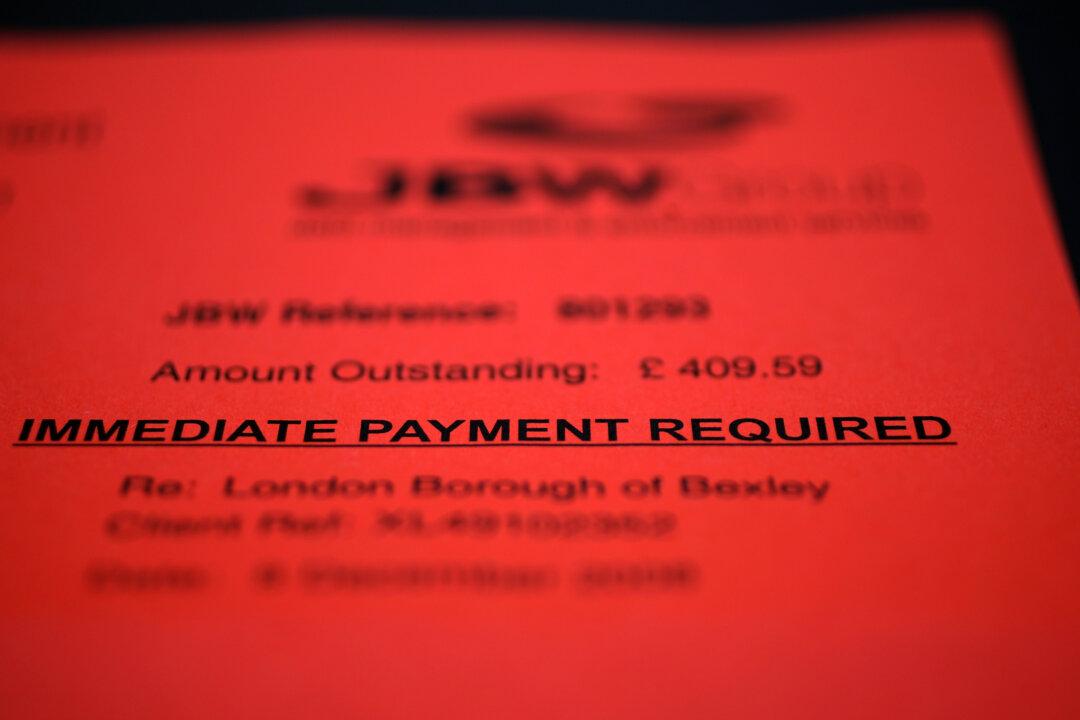

When Jeff, a retired marketing consultant from Chicago, was closing on his home sale, he received a new set of instructions at the last minute on where to send several thousand dollars in closing expenses. At first blush, the email looked legit with an official-looking logo and professional language specifying the amount owed and itemized expenses. But one thing caught his eye: The email address looked strange. Just to be safe, he called his mortgage broker.

“Don’t do that!” his broker told him in an alarmed voice. It was a scam. If he hit “send,” his closing fees would go to a thief who had been monitoring his emails. “I was a keystroke away from losing thousands of dollars,” Jeff recalled.