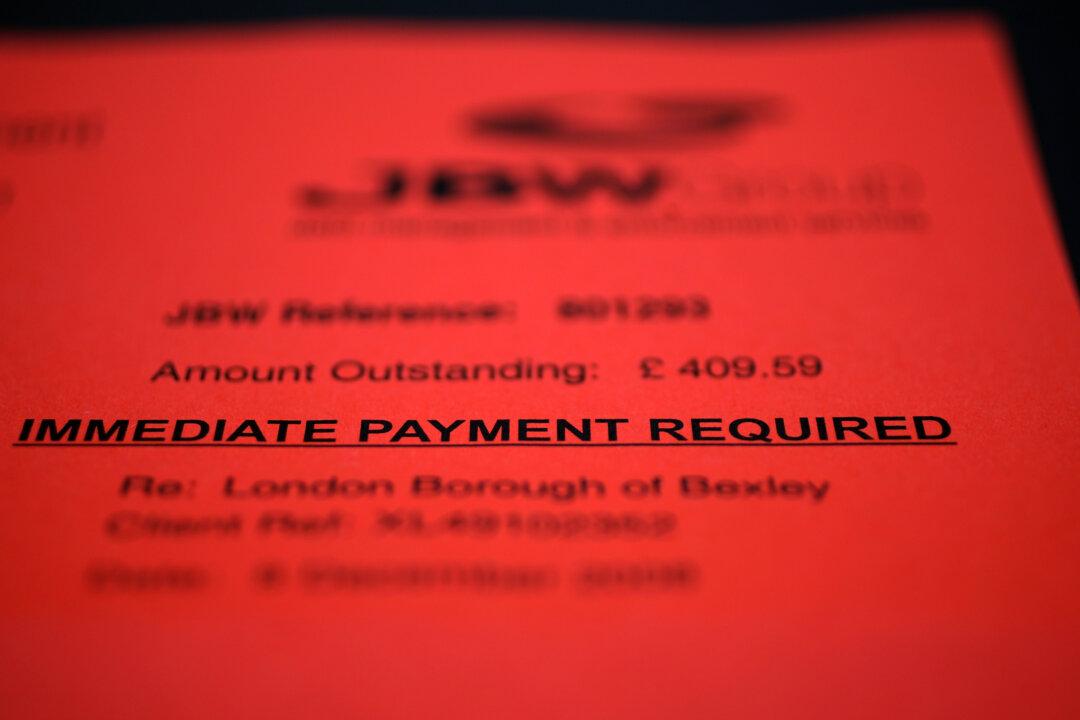

Like many retirees, Jesus Nunez knew he was due a pension but was having a hard time tracking it down. Now 66, the Burbank, Illinois, resident had worked as a painter and garage worker for the Checker Taxi Co. Inc from 1978 to 1986 and then another year for its successor concern. But when Checker Motors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2009, he never got a notice about his anticipated retirement checks. He figures he’s due about $300 per month.

“They didn’t tell me anything about my pension,” says Nunez. “Later someone said they lost my records.”