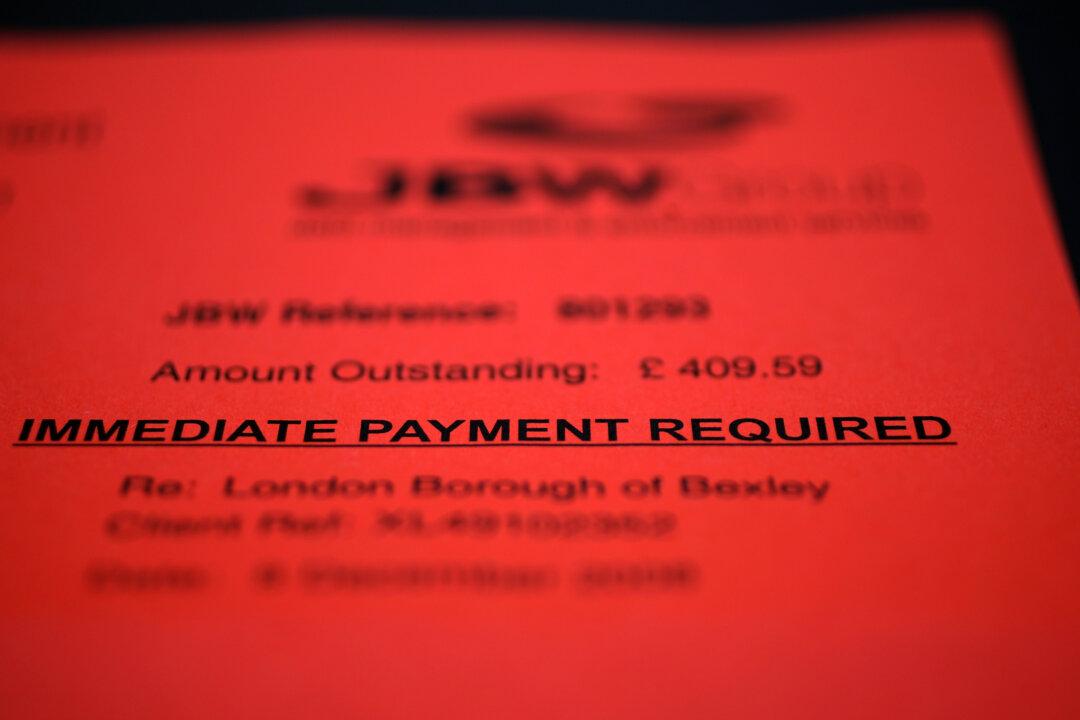

The email from “Norton Protection” said I owed $999.99, which was “charged successfully and it will appear on your bank statement in 24 to 48 hours.” Although I have an account with a leading cybersecurity company, I’ve never paid that much for its products. To “cancel” the charge, I was instructed to call a number, conveniently highlighted in yellow.

All it took to bird-dog my fake debt email was a simple search-engine query of the invoice’s telephone number. It was based in Hawaii. Unfortunately, perhaps, for the real employees of Norton’s help desk, they are likely not stationed in the Aloha State.