News Analysis

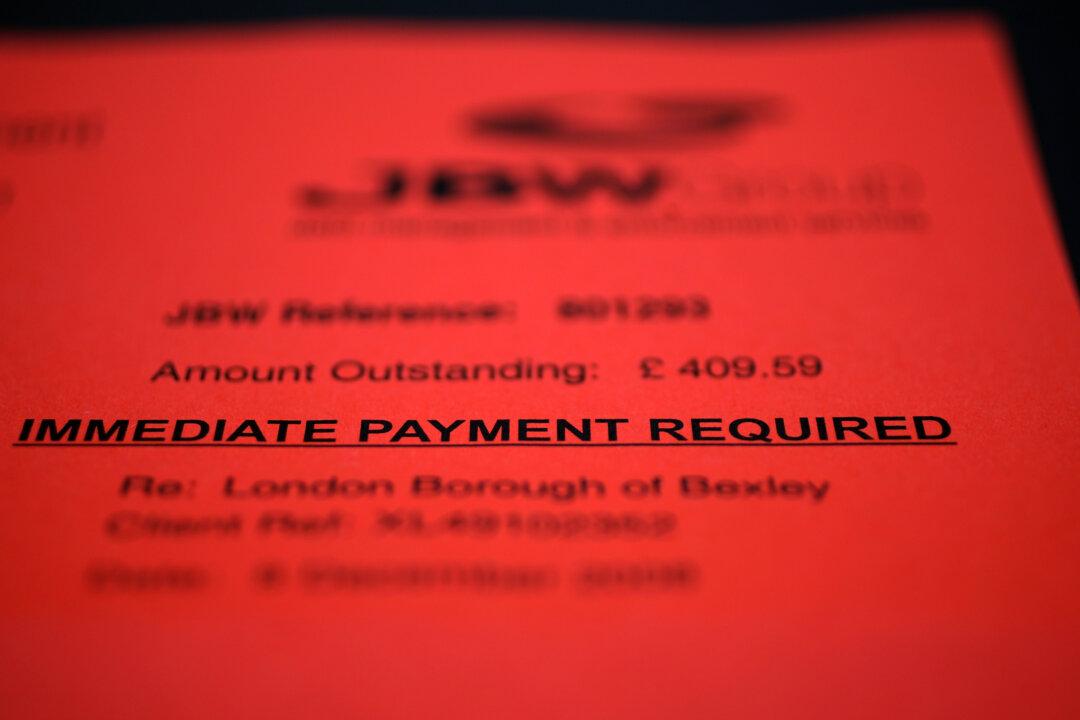

Fretting over your 401(k) lately? For all the current turbulence in these retirement plans—from their rocky recent market performance to asset managers’ politicization of their investments through the “environment, social and governance” agenda—the main problem lies in their flawed design decades ago, a range of retirement experts say.