“Witness” was first published by Random House in 1952, at the height of the Cold War. A 50th anniversary edition was published with a new foreword by renowned political author and commentator William F. Buckley Jr. (1925–2008). Buckley met the author, Whittaker Chambers, two years after the publication of the book and employed Chambers in 1957 as a senior editor for his National Review magazine. While the book has been reprinted since then, the last reprint occurred in 2014 by Regnery. Interested readers can find it in many forms, everything from a first edition to an e-book.

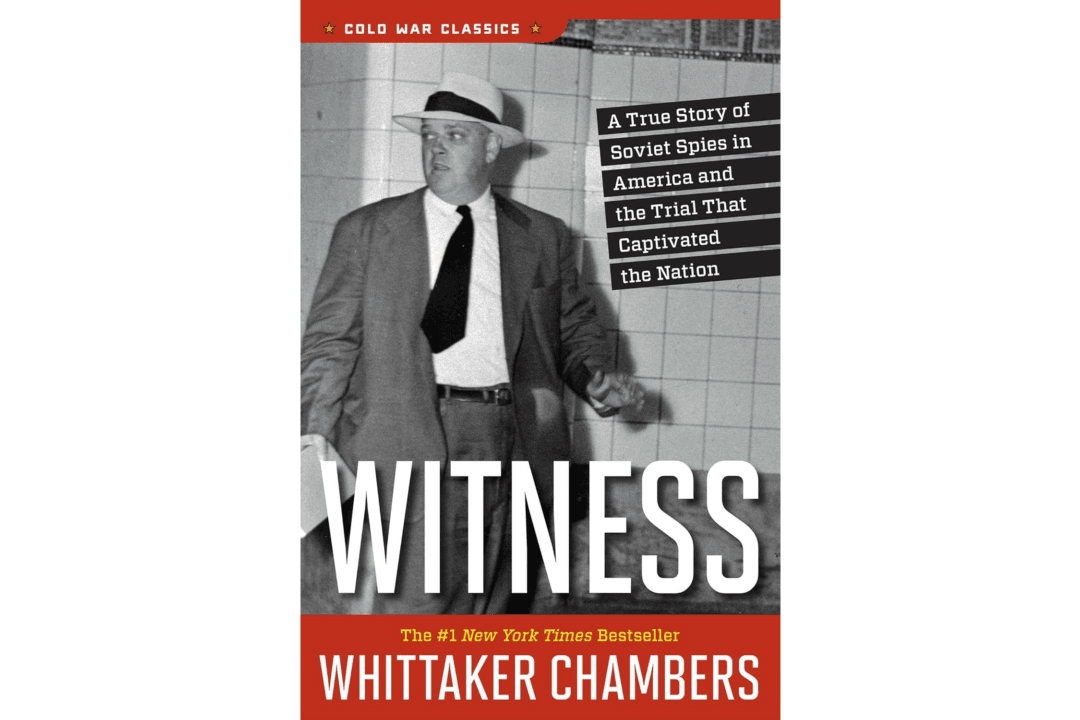

Whittaker Chambers, American writer, editor, and Communist party-member-turned-defector. Public Domain