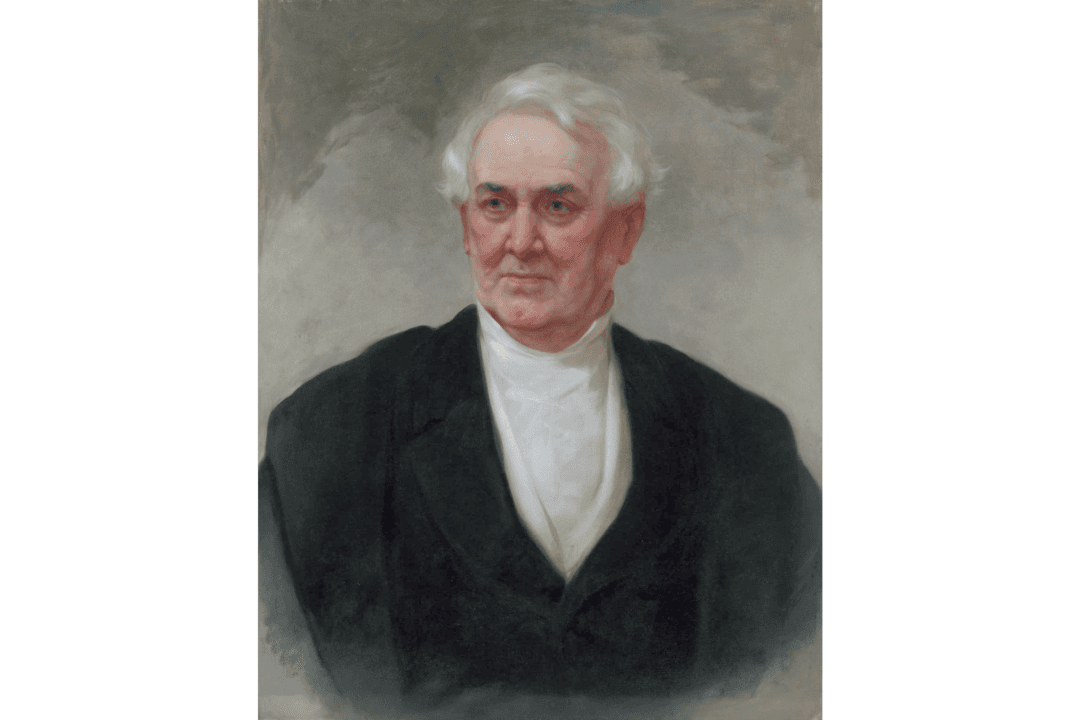

William Wilson Corcoran (1798–1888) grew up in the nation’s capital. He was the son of Irish immigrant Thomas Corcoran, who became a wealthy merchant and also had success politically, being elected multiple times as mayor of Georgetown. The Corcorans, despite their comfortable lifestyle, were still subject to the ills of the age as only half of their 12 children survived to maturity. William Corcoran, however, would live a long, industrious, and prosperous life.

Corcoran received a fine education, but only attended college for one year. After his short stint at Georgetown College (now University), he went into the dry goods business. The business lasted for several years until he was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1823, due in large part to the aftermath of the Panic of 1819. His father had retained his wealth and estate, which Corcoran began to manage. His gift for business and finance eventually led him to the banking industry. From 1828 to 1836, he worked for several banks, including Georgetown’s Bank of Columbia.