William Henry Pickering (1858–1938) was born in Boston to a prominent American family, one whose roots went back to 1636. Arguably, the most prominent member in the Pickering lineage was his great-grandfather, Timothy Pickering (1745–1829), who had been a colonel, adjutant general, quartermaster general, and a member of the Board of War during the American Revolution. He served as a delegate during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. In the new republic, he was a representative, senator, postmaster general, secretary of war, and secretary of state. The fame of his descendant William Henry Pickering, would not be among American politicians, but rather among the stars—literally.

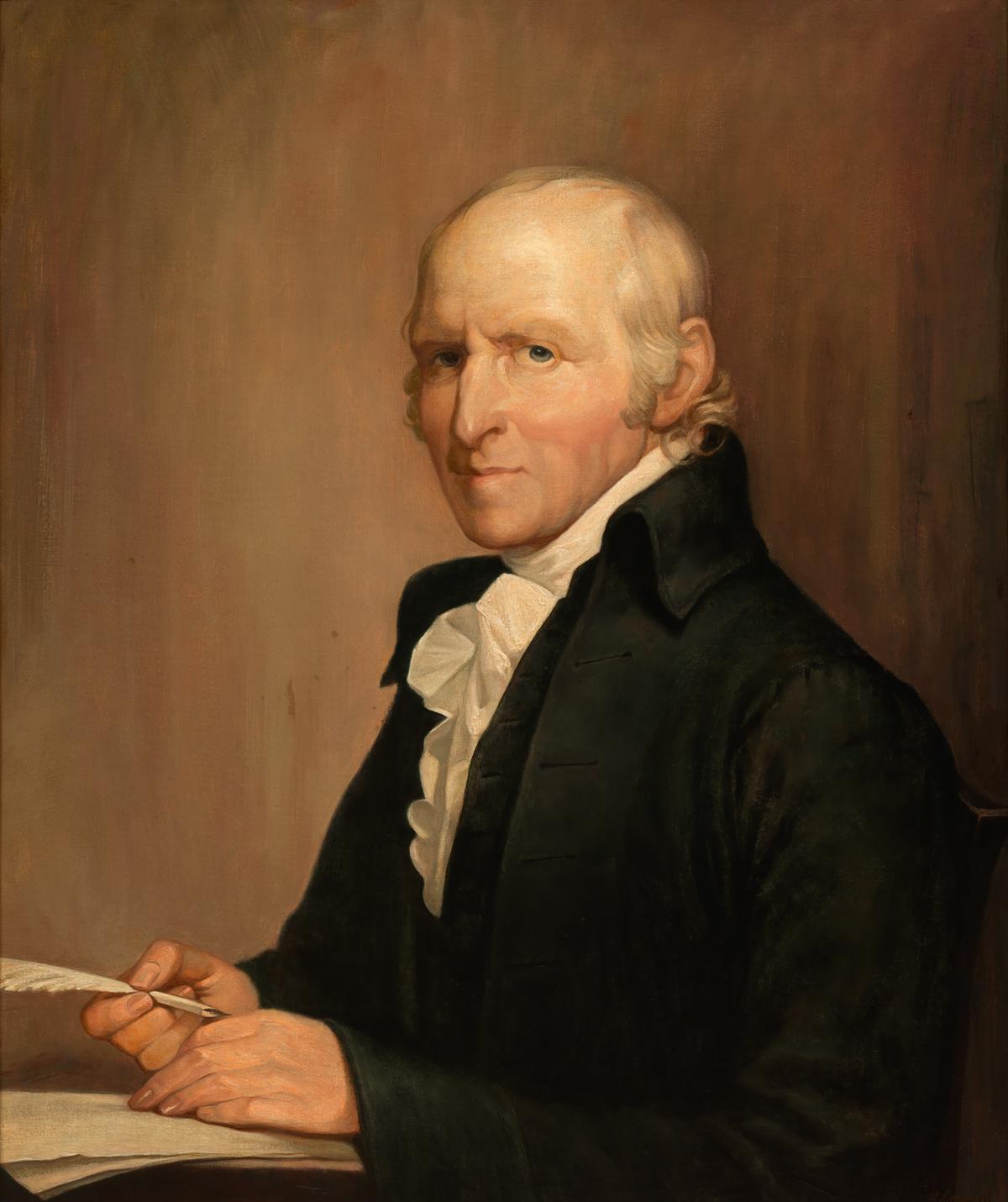

A portrait of Timothy Pickering as secretary of state, before 1828, by Gilbert Stuart. Public Domain