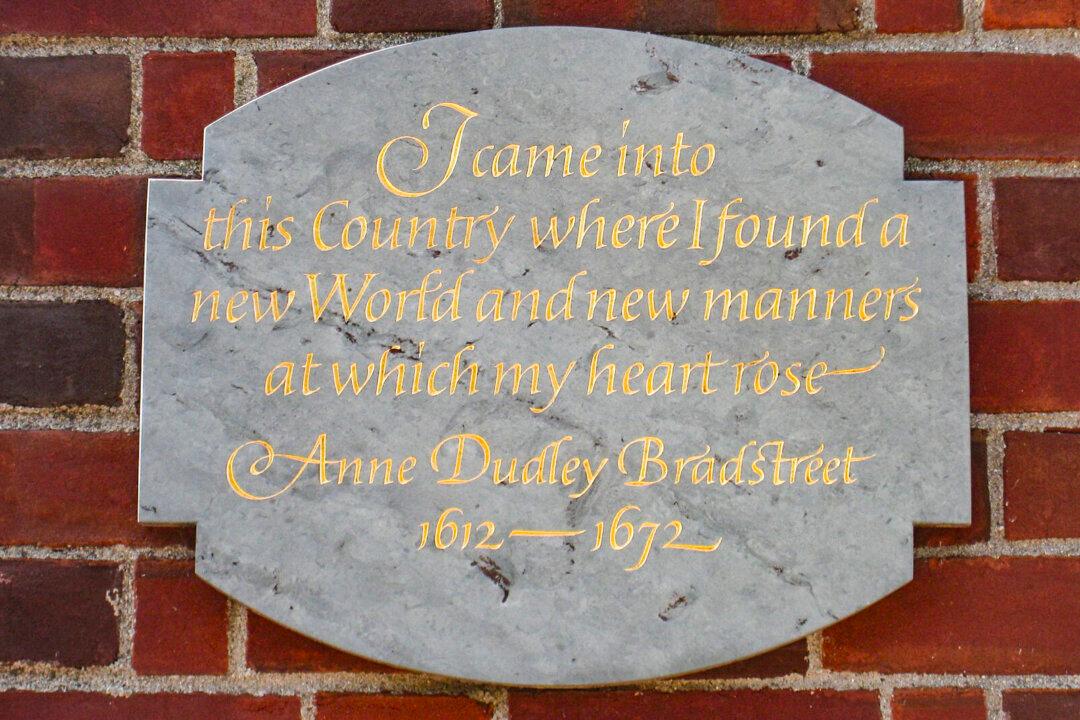

In the spring of 1630, 18-year-old Anne Dudley Bradstreet (1612–1672) boarded the Arabella along with Simon, her husband of two years; her father; and other members of her Puritan family to sail from England to the Massachusetts colony. As she was well-educated from early childhood and raised in an aristocratic household where her father served as steward, the close quarters of the ship and the bad weather during the crossing must have come as a shock to Bradstreet.

Even more shocking were the conditions that awaited her arrival in the New England colony. As Anne’s father, Thomas Dudley, wrote to the wife of his former employer, the Earl of Lincoln: